THE REALITIES OF TUBELESS ROAD TIRES

I’ll admit it, I didn’t get excited about using tubeless road tires when they first became available for road bike wheels. I was quite comfortable setting up my tires with tubes, had a go-to tire model that was comfortable, handled well, was plenty durable, seemed fast, and ranked well in rolling resistance tests. I seldom flatted, and when I did, it was an easy fix.

So why try tubeless road tires? Everything I read said they were harder to get on my rims, took a lot of work to inflate and seal, made a mess, had higher rolling resistance than clinchers, and if you ever did get a flat on the road, fixing a tubeless tire was not going to be easy.

Seems that I was not alone. Even though wheel makers were selling more and more road wheels that were tubeless-ready, most road cyclists weren’t ready for tubeless. In 2015, no more than 10% of us were riding tubeless bike tires.

And then, it happened.

Well actually, several things happened.

Tubeless valves with removable cores became the standard valve shipped with new tubeless-ready road wheels. Injecting sealant through your valve once your tire was fully mounted instead of pouring it into your partially mounted tire made for little or no mess.

Rolling resistance tests of tubeless road tires began to show equal or better results than the best clincher tires with butyl and even latex tubes.

Better tire compounds made the leading tubeless bicycle tires for the road as supple and sure-footed as clinchers.

Wider and better designed tubeless road rims and tires made many tires as easy to mount, inflate, seal, and stay sealed as clinchers. They required no more than a standard track pump in an increasing number of cases.

The adoption of wider tires and rims and lower inflation pressure for added riding comfort also made clinchers less attractive. At lower pressures, clinchers pinch flat more easily than when more firmly inflated as the tube rubs against the tire. That negative and the positive of sealant quickly repairing most tubeless punctures made clinchers less attractive.

Increases in inflation pressure from the heat generated by braking on carbon rim was no longer a concern if you were using the increasingly accepted and available number of disc brake wheels. These provide a more consistent seal between the tire and the wheel when the rim’s temperature wasn’t changing the way it does when rim braking.

Finally, a lot of good road wheels started coming not just tubeless-ready or tubeless compatible but “tubeless optimized”. No need to tape; a pre-installed plastic strip covered the entire rim bed. The rims were wider, the beds had a center channel to make it easier to get tires on. Small channels or “bead locks” were added along the edges of the rim bed to keep the tires in place and keep them from “burping” air under hard cornering.

For several years now, most of the investment in tires and wheels has gone into advancing tubeless rather than clinchers. Standards-setting groups have also been working to make tubeless road tires and wheelsets work more interchangeably.

All of this has led to more and more road cycling enthusiasts using tubeless road tires, and more and better tires and wheelsets getting introduced.

For those who have considered going tubeless, those ever-present questions among roadies – do I have the best gear and what is real amongst all this hype – has crept into yet a new area of our cycling consciousness.

I’ve been riding, evaluating, and writing about tubeless road tires and wheels for several years now and trying to separate the tangible benefits from the BS. For this post, I’ve assembled pieces from past ones about tubeless and made major additions and revisions to my tire evaluation and rating criteria.

This post accompanies my new reviews, ratings, and recommendations of the Best Tubeless Tires for road cyclists. If you’ve adopted tubeless road tires, been thinking about it, or had a bad experience that caused you not to want to think about it ever again, you may benefit from my updated and improved explanation below of where things stand now before you buy your next set of tires.

Related Reviews

WHERE I’M COMING FROM

If you aren’t familiar with this site and my reviews, know that what I try to do is share my road cycling enthusiast’s perspective on gear and kit with fellow roadies. To shield the site and me from the influences of the industry, I maintain policies that help me and my fellow testers keep our independence and allow me to write unbiased, in-depth, comparative reviews.

I buy or demo and return or donate anything I test, don’t go to industry trade-shows or on any supplier-expensed product introduction trips or site visits. You will not see any advertising for cycling products or anything else on this site. I don’t accept articles, announcements or any content paid for or submitted by companies, stores, PR firms, or guest authors, or charge you for any content on the site. I don’t publish new product announcements, don’t regurgitate company talking points about their gear, and keep an arm’s length relationship with suppliers. While I use social media to share what’s happening on the site with readers, I don’t engage in influencer marketing.

All of the costs, gear purchases, and other expenses related to this site are covered out of my pocket, from donations, and when readers buy something using the links on the site, some which generate an affiliate commission.

With that as preamble, know that I’ve come to love the performance benefits tubeless brings me. More comfortable rides, better handling, and almost no flats top the list of why I’ve converted to tubeless.

At the same time, I know from my own experiences and those readers have shared with me that the adoption of tubeless road tires and wheels for many cycling enthusiasts has not been easy. There are many issues that cause some of you to never try or strongly dislike tubeless.

From what I can tell, our experiences installing and maintaining tubeless road tires have been the key to whether we’ve adopted tubeless, stayed away from it awaiting improvements, or sworn it off for a lifetime. I get that while we all love riding, we adopt new technologies and products differently.

I’m not attempting to convince you to adopt tubeless bicycle tires but rather to inform you about them at a deeper and more honest level than what you see from many sources with an agenda. Hopefully, this will help you make decisions about how well tubeless might suit you and give you a better understanding of what matters most in choosing between different tires.

EXAMINING THE ARGUMENT FOR TUBELESS ROAD TIRES

Compared to clincher tires with inner tubes, tubeless road tires have been promoted for their

1) better puncture protection

2) greater comfort

3) better handling

4) lower rolling resistance

5) lighter weight

While the data I’ve seen, my experience, and physics suggest you can get all of these benefits from going tubeless, they are also all debatable. Depending on your riding situation and what’s most important to you just among this list of benefits and regardless of other considerations, you could as easily conclude that a clincher tire is equivalent or better for you than a tubeless one.

A few examples illustrate this point. I created a list of the lowest rolling resistance tires with puncture belts and a minimum level of puncture resistance from Bicycle Rolling Resistance, one of several labs that do tire testing. While many of the lowest rolling resistance tires on this list are tubeless, both tubeless and clincher tire types are well represented.

Further, in the way they measure it, there are only 3-4 watts of rolling resistance difference for all but the lowest and highest rolling resistance tires on the list of nearly 25 top tires at the pressures most of us will be riding. Puncture resistance differences are also equally small.

Using and maintaining the right amount of sealant in tubeless road tires will close most punctures that would force you to replace the inner tube on a clincher tire with a similar thickness and puncture belt. But, if you aren’t into keeping up with sealant maintenance (or maintenance in general) or you ride on roads where you’re likely to get larger than normal punctures in the bottom or side of your tires, you’ll likely need to install a tube after a puncture regardless of whether you are using a clincher or tubeless road tire.

Comfort and handling benefits follow a similar “it depends” logic. Lowering your tire pressure will provide you more comfort on the road and better handling up to a point. You can obviously lower the pressure of any tire regardless of whether it has a tube in it or not.

However, clinchers are more likely to pinch flat as you lower your tire pressure whereas tubeless bicycle tires won’t have this concern as you search out a pressure that will give you the best comfort and handling. The test data also shows that the difference in rolling resistance also favors tubeless road tires the further you reduce your pressure.

Then again, if you prefer to run your tire pressure at more traditional (i.e. higher) levels, the relative pinch flat and rolling resistance benefits of tubeless won’t come into the equation.

As to weight, I’ve run the numbers on tubeless and clincher tires intended for the same riding objectives. In reality, a) there’s little weight difference between the complete set-up of each (clincher tire and tube vs. tubeless tire, sealant, and valve, and b) the differences are not big enough for most road cycling enthusiasts to notice it on the road. You can see the details later in this post.

So why do I favor tubeless road tires?

As I wrote above, it’s about the relative comfort, handling, and puncture protection benefits they offer me. This is especially the case as I’ve moved from 17C wheels and 23mm tires to 19C and 21C hoops with 25mm and 28mm rubber inflated at 20 to 50 psi lower pressures. (Yep, I used to inflate my clinchers to 100-110psi even though I’m only 150lbs.)

I’ve also developed the skills to install and service tubeless road tires as easily as I do clinchers. And, I expect the tubeless experience and performance is only going to get better because that’s where the competition is between manufacturers now and where the R&D money is being spent.

CYCLING TECHNOLOGY AND TUBELESS ADOPTION

There’s been a lot said and written about tubeless vs. clincher tires for road bikes. If this seems somewhat familiar to the earlier debate between clinchers vs. tubulars, it’s likely because it also mirrors the arguments we cyclists have had between disc brakes vs. rim brakes, electronic vs. mechanical shifting, and carbon frames vs. aluminum, titanium, and steel frames.

New technology creates debate and draws attention. It’s what opinion setters and writers like to talk about, what product makers like to promote, and what cyclists like to learn about and discuss among themselves.

That’s all good and interesting. But, I’m not going to debate it any further beyond what I’ve written above. Both tubeless and clinchers work. One may be better for your situation and priorities.

I do want to put a different lens on the debate and explain how people approach new technology. This may help you understand where you fit in the broader context of what’s going on and how the tubeless vs. clincher tire evolution may play out.

Some riders embrace whatever is new and seems better than what they’ve been using or doing. Most will join their fellow roadies once things have been proven out at least somewhat. Others resist change as long as they can, perfectly satisfied with what already works for them.

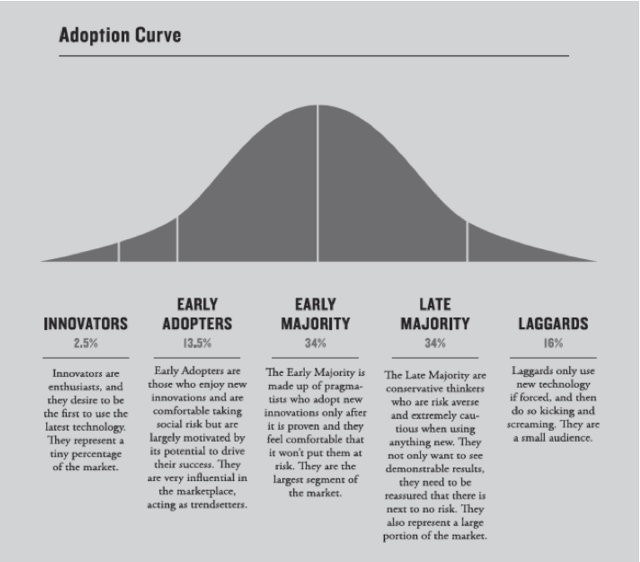

Technology adoption is an intensely studied field of study as it has huge commercial and even macro-economic implications. Researchers have found that each of us falls somewhere on what’s called the Rogers Adoption Curve that explains when people start using innovative products based on new technology.

If you’re not familiar with this line of thinking, here it is. Take a look at the descriptions and see which best describes you.

If you fall on the left side of the curve, there’s a good chance you are already a road tubeless convert. Most Innovators and Early Adopters are likely using road tubeless now. Anecdotally, it also looks like some of the first of the Early Majority types are riding tubeless.

The interesting part, at least for me as one who evaluates, critiques, and recommends cycling products and perhaps you as one who buys cycling products, is how far along this adoption curve we’ll get with tubeless road tires and what percentage of cyclists will end up rolling on them.

I could posit that we didn’t get very far into the Early Majority (EM) with carbon rim brake wheels but that most EMs will adopt carbon disc brake ones as will some in the Late Majority. The declining price for carbon wheels and the slowing innovation and new product introductions of alloy ones suggests that carbon will eventually become the dominant wheelset material when most of us are riding road disc bikes.

Power meters and electronic shifting products are likely both into the late majority but neither have a commanding market share. Because most enthusiasts don’t train using power or don’t care about what their power output is, most aren’t going to spend the money on a power meter. Electronic groupsets provide a lot of benefits that most would like but their price makes for lower adoption rates with every segment of adopters on the curve.

Tubeless road tires? My guess is that it will take until 2022 before road tubeless technology advances to “proven” in the eyes of many roadies as further developments make their benefits more evident and there is no added hassle compared to clinchers. At that point, I expect some in the Early Majority will begin to adopt it.

Even with that and similar to the travails of carbon rim brake wheels, it may take another 2-3 years more before the bad experiences some have undergone recede in enough Early and Late Majority riders’ consciousnesses for road tubeless road tires to outsell clinchers.

So for all of you who prefer to put tubes in your road tires, rest easy, they will likely remain on the scene for many years to come.

[promo_block]

EVALUATION AND RATING CRITERIA FOR TUBELESS ROAD TIRES

I first published a comparative review of tubeless road tires in July 2018. Since then, the world of tubeless products has expanded and improved a great deal. So too has my experience with tubeless road tires and wheels and the understanding of how to produce better speed, power, handling, and comfort using them.

In keeping with this, I’ve expanded my evaluation approach and revised my criteria for rating tires to give you better recommendations and ways to make a more informed decision on which tubeless road tires are best for you.

What follows are descriptions of the criteria that I believe matter most and least, in order of their importance.

What Matters Most

1. Aerodynamics of the rim-tire combination – Aerodynamics has always been important in cycling. Our appreciation of its contribution to a rider’s speed and power output, compared to things like weight and rolling resistance has grown and changed the design of bikes, helmets, clothing, components, wheels, and tires a great deal, especially in recent years.

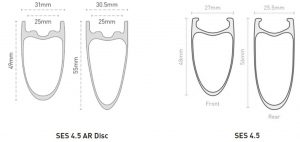

Wind tunnel observations from Josh Poertner, now head of the company Silca and formerly Zipp’s lead engineer during the initial Fieldcrest aero wheelset development around 2010 led to what he called the Rule of 105. He boiled it down to saying that “the rim must be at least 105% the width of the tire if you have any chance of re-capturing airflow from the tire and controlling it or smoothing it.”

By controlling or smoothing the air, it continues along or sticks to your rims to reduce aerodynamic drag and give you lift like an airplane wing. At less than 105%, air diverts away from your rims and you get limited aero benefit from those 40mm and deeper carbon wheels you and I spent so much on.

The technical and market success of Zipp’s Fieldcrest wheels and those from HED developed at the same time and drawing from findings that went into a patent that engineers from the two companies co-authored showed the way for carbon wheelset designers and suppliers across the industry. The Zipp and HED rim shapes were imitated and later advanced following the Rule of 105, often using the popular Continental Grand Prix 4000 tire in the design effort, to develop aerodynamically competitive wheelsets.

Of course, the computational fluid dynamics or CFD that wheel designers use today allows them to test a wide range of variables to come up with the most aerodynamic wheels. That said, many leading wheelset and tire companies still acknowledge the importance of the rim to tire ratio in getting the fastest setup.

Note that in his 105% calculation, Poertner was measuring the actual width of the tire once installed and inflated on a rim and not the labeled size on the packaging or side of a tire. The actual installed and inflated width is almost always wider than the labeled size, usually in the range of 1-3mm depending on your tire and rim choice.

What about where you measure the width of the rim, as some rims vary in width from the brake track to the center? Poertner writes about applying the rule “almost anywhere on a deep rim.” Further, he describes the trade-off between rims that are wider and offer better aerodynamic efficiency when the width is focused on the brake track vs. getting improved handling and reduced crosswind effect when the rim is widest at the center.

Rim profiles seem to be varying more than ever and now include a fair number of slightly rounded V-shaped rims, blunt nose U-shaped ones, VU shapes or those that start with a V shape at the spoke bed but quickly adopt a parallel or U-shaped profile, and still, some with the toroidal or oval shape the original Zipp and HED aero rims used.

To try to deal with all of this, I’ve measured the rim and applied the rule at the “brake track” (or where one would be on a disc brake rim if it was using a rim brake) and at the widest point when it’s not at the brake track.

There is little to be gained going above 105%, up to 2 watts at 108% from a study sited in Poertner’s post. But go below 105% and you can lose the aerodynamic “free-speed” benefits that can range up to 20 watts.

After reviewing numerous reports with different protocols and points of view from Hambini to Zipp to FLO/Anhalt to Aerocoach to a lot of “joshatslica” comments on Slowtwitch – how’s that for range? – I estimate you could lose from 5 to 15 watts with your rim-tire width combination below the 105% ratio if your wheels are in the 40-65mm depth range and you are riding at 20 to 25mph (32 to 40kph). The exact loss would depend on variables like your actual rim to tire ratio, internal rim width, rim depth, rim profile, yaw angle, and more.

This means you can lose somewhere between 20 seconds to a full minute over a 25 mile, 40 kilometer solo ride or time trial course. On a typically longer competitive group ride, distance event or road race, you’re talking about riding at a 5-15 watt higher power level for several hours to keep up with the pack and avoid losing minutes.

I don’t know about you, but I’d rather not work that hard that long as punishment for picking the wrong tires.

Because aerodynamic drag increases exponentially with speed, it takes you eight times more power to overcome the drag to double your speed. So getting above that 105% can save you lots ‘o watts of effort when you want to go faster. And the faster you go, the bigger the gain or loss from being on the right or wrong side of this rule.

For those of us looking for the “best” tubeless road tires, the challenge living by the Rule of 105 and saving those precious watts comes from picking tires for the wheels we have or are planning to get in a market where the sizes and shapes of tubeless road tires and wheels are both unique and regularly updated, but not always in a coordinated way.

Hookless rims, which I believe we’ll see more of in the next round of wheelset introductions, further complicate your tire options as some tires use bead materials that hold better in hookless rims than others. Tubeless road tires with different diameter beads and rims with different diameter bead locks those beads go into can also cause real installation challenges.

Newly introduced tubeless road tires are inflating closer to their labeled size but still vary in actual width on rims with the same inside width but different outside widths. And, as tires stretch when you ride them more, they also get wider.

Today, as wheelset designers acknowledge that further changes in rim designs are yielding diminishing aero returns, the rim-tire relationship is playing an increasingly important role. To better optimize this and manage the challenges mentioned above, more wheelset companies are making tires intended to work best with their own rims including Specialized/Roval, Mavic, Zipp, Bontrager, and ENVE.

While the aero performance of the rim-tire combination is a priority, some of these tires are designed to achieve other performance goals (e.g. better handling and grip) that may result in providing less aero benefit than tires made by those who don’t also sell wheels.

And while updated and emerging ETRTO standards aim for better tubeless tire and rim compatibility regardless of who makes them, that’s clearly not the case yet and can further frustrate your choice for combining individual rims and tires to make the best aerodynamic solution.

I’ve always measured the tires and wheels I test rather than take the width (and weight) claims from manufacturers at face value. To get a better handle on the potential aerodynamic gains or losses of tubeless road tires without doing wind-tunnel testing, I’ve upped my game by measuring as many combinations of tires and wheels as I have available whenever I get a new one of either in for testing.

Needless to say, my hands and shoulders are getting a better workout doing this than anything I’ve ever done on my bike. The results have been quite revealing.

While I share specific rim to tire width ratios in my review of tubeless road tires (here), there are a few key take-aways.

- While 28mm tubeless road tires are promoted for their improved comfort and handling, most don’t abide by the Rule of 105 unless you have wheels with an outside rim width of at least 30mm.

- Most 25mm labeled tubeless road tires meet or exceed the Rule of 105 when installed on 19C rims that have at least a 28mm outside width and on 21C rims at least 29mm wide.

- If your rims are narrower than 27mm and you prioritize speed on your aero wheels, use 23mm tires.

Note that all of this applies to the front rim-tire combination. The rear wheel contributes far less to your aero performance as it shielded by your frame and subject the “dirty” air created by your legs. There’s little aero penalty and certainly, a comfort bonus going with a rear tire a size larger than your front one.

2. Road feel – The quality of the ride or “road feel” you get from a set of tubeless road tires usually comes down to how you experience of their comfort, handling, and grip.

Beyond the tire design, materials, and construction, many factors can play a role in that road feel experience. The tire pressure and the wheelset’s lateral stiffness and vertical compliance play important parts as does how aggressively and fast you ride, the road surface you’re on and the terrain and handling required on your route.

So yeah, road feel can be pretty subjective.

However, the better you like your tire’s comfort, handling, and grip, the more confidence and enjoyment you’ll have riding it and likely, the faster, more aggressively, and longer you’ll ride.

So in addtion to being subjective, road feel is a super important criterion if speed and endurance are important to you and most of our fellow cycling enthusiasts.

To try to make this a little less subjective or dependent on my take alone, I’ve combined my evaluations with those of fellow testers Nate and Miles who have different rider profiles than me and each other to see if and where we share some common experiences on the elements of each tire’s road feel.

And to try to further bracket some of the subjectivity, we did our latest round of tubeless road tire evaluations with 25C size tires, on a half-dozen models of aero road disc wheels, and with a renewed focus on tire pressure.

Tire pressure is probably the biggest determinant of road feel. There’s been a lot of research published in recent years showing how we roadies have historically ridden over-inflated our tires and suffered energy or “impedance” losses as our bodies absorb the road vibrations. These are greater than the losses in rolling resistance when tires deflect and recover to absorb imperfections in the road surface.

Rather than diving into all the testing and science (it’s here if you want to), I’ll simply tell you that getting your tire pressure right will:

- smooth out your ride and save you energy or watts you can use to put into your pedals for more speed over the whole ride, at key points during it, or just to ride longer at a lower power level, and

- increase your speed without expending any additional energy or watts

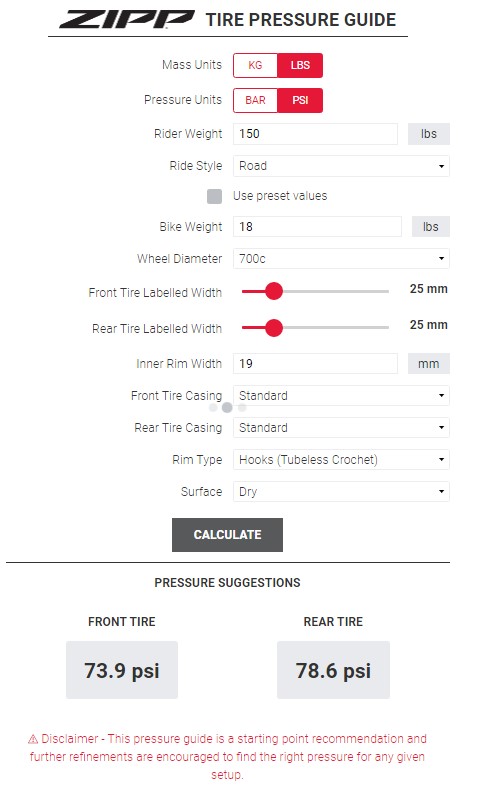

Now that I’ve hopefully gotten your attention with the word speed which works with roadies nearly as well as, or maybe better than the word sex, let me encourage you to use one of the modern tire pressure charts or calculators at these links from ENVE, Zipp or Silca that guide you to the right tire pressure for you.

Here’s an example of the pressure suggested for one of my recent rides:

As you can see, weight, tire width, rim width, and other factors can affect the recommended tire pressure. Using a guide like this and staying within a few psi of what it recommends, we can more effectively separate out tire pressure as a variable in differentiating between the comfort, handling, and grip between tubeless road tires.

While it’s hard to know exactly what separates the road feel of one model of tires than another, it’s likely that compound, casing dimensions, thread count, layer materials, construction, and other aspects of a tire’s unique alchemy contribute to its ultimate road feel. Research has also shown that a rim-tire combination of less than 105% also negatively affects handling, likely because the tire is not adequately supported by the rim.

3. Rolling Resistance – Tire makers mix some combination of organic polymers, man-made synthetic materials, silica, and who knows what else, all to reduce the friction and improve the grip from tires when they are doing their thing on the road. The less friction, the less energy required for the tire to return to its shape (aka “hysteresis”) after it deforms or deflects from the unevenness in the road surface. All of this goes into lowering a tire’s rolling resistance.

On the other hand, a compound that returns the tire to its shape a little slower provides better grip and handling. Some tires use a lower hysteresis compound in the center width of the tire to provide low rolling resistance and a higher hysteresis compound in the sides of the tire to provide better grip and handling when you are leaning into turns.

So there are trade-offs between rolling resistance and the handling and grip parts of road feel.

Rolling resistance has become a popular decision criterion for many riders these days. With several labs publishing their results, it certainly is very quantifiable (and marketable).

The lower the rolling resistance the better. For example, 11.6 watts of rolling resistance is less and therefore better than 13.8 watts. Simple, right?

Well, rolling resistance tests don’t exist in a vacuum and the number that comes out will vary depending on a lot of factors. It changes depending on the tire width and inflation pressure. Actual rolling resistance outside the lab differs based on the road surface you ride.

Test numbers depend on the surface of the drum used in the lab to emulate it. The width of the rim the tire is mounted on, the weight applied to the wheel, the speed at which the wheel is tested, the amount of sealant or type of tube used, the testing temperature, and the testing protocol all affect the rolling resistance number that a test produces.

So, rolling resistance scores are more relative within a specific testing protocol than absolute between testers or tires.

Allow me to share the fortunately and unfortunately soliloquy I’ve been working through to be able to say which tire has the best rolling resistance, which is second best, etc.

Fortunately, there are some very thoughtful people who focus intensively on rolling resistance and whose results you can learn from. I’ve worked through the published results of most of them for the tires in my reviews to come up with some relative rolling resistance rankings.

Jarno Bierman at the site Bicycle Rolling Resistance (BRR) and the test lab at Tour Magazine (German language, subscription required) regularly conduct and publish independent tests of tire performance and make them available to readers of their sites.

The private service Wheel Energy Laboratory does rolling resistance testing principally for their tire maker clients but has done them for Velo News and Bike Radar for an article each have run in past years. Aerocoach has published results of rolling resistance of various tires mounted on the wheels they make.

BRR, Tour, Wheel Energy, and Aerocoach each test a little differently and produce different absolute rolling resistance numbers.

For example, the original 25C Schwalbe Pro One had a rolling resistance of 11.6, 12.8 and 14.8 watts at 100psi, 80psi, and 60psi inflation pressures respectively in BRR’s tests. They use a 42.5 kg load at 18mph/29kph on a diamond plate drum with a 17C wide rim.

For the same tire, Wheel Energy came up with a 30.2 watt rolling resistance at 80 psi but with a 50kg load on the tire rotating at 25mph/40kph on an unevenly rolling diamond plate drum using a 19C wide rim.

Tour uses an actual road surface section and oscillates two wheels in a pendulum fashion loaded with 110kg which they’ve calculated translates to a combined rider and bike weight of 85kg traveling at 30kph. They come up with 67.4 watts of rolling resistance (or 33.7 watts per wheel) for the original Schwalbe Pro One Tubeless tested at 6bar/87psi. Yet, they don’t specify the rim width used for the tests. Judging from the wheels they were separately testing around at the same time, I expect it was a 17C wide rim.

You still with me?

Unfortunately, unlike the original 25C Schwalbe Pro One, all the current tires that you or I might be interested in haven’t been tested by each of the testers. Further, so that they can determine the improvement in tires from one generation to another, most published testing is being done on 17C rims, far narrower than the 19C, 21C, and even 25C rims that are more commonly being made for road bikes today.

With a few exceptions, the rolling resistance of tires made for a similar riding purpose like those we roadies buy for training or racing and that have a puncture belt are not more than a few watts different (low single digits) within each one these testing protocols.

Fortunately, there’s some overlap between the tires they have tested and from that, I would hope to be able to do some relative rankings not just within but across testing protocols.

Unfortunately, the testers and their unique protocols sometimes but don’t always produce the same relative rankings. Disappointing since rolling resistance varies linearly with speed.

Sorry to put you through all of that but I just wanted to provide you some context and discourage you from picking a tire based a single published rolling resistance number or test ranking for a single source. Unfortunately, it’s just not that straightforward.

Of course, actual rolling resistance outside the lab differs based on the road surface you ride.

With all that said, here’s the really important bit: Because rolling resistance increases linearly or at the same rate as your speed increases while aerodynamic drag increases exponentially, rolling resistance matters relatively less than aero drag starting around 12 miles per hour and increasingly less as your go faster.

This chart courtesy of ENVE shows the relative contribution of each at different speeds.

Of course, aero drag from your wheels is only about 10% of total drag with the majority coming from your body and some from your bike.

But at the speeds we roadies ride, my take-away is that rolling resistance is both less important than aero drag or road feel and there’s little difference between most of the training and racing tires with puncture belts that we use. Putting on too wide a tire that doesn’t meet the rule of 105 on your aero wheels can more than overcome the small differences in rolling resistance between the tires we use.

I’m not suggesting that rolling resistance isn’t important. Rather, I’m encouraging you to put it in the context of the other criteria used to evaluate and choose a tire.

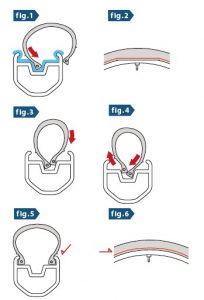

4. Installation – For those of you who have been tubeless converts for several years or those who remain interested but have held off because of some of the horror stories of installation difficulties, I can tell you that a lot has changed for the better in just the last few years.

Newer, wider, deeper road tubeless wheelsets have a center channel in the rim bed that is a few millimeters lower than the rest of the rim bed. They also have “bead locks” or shallower, narrower channels running inside the rim walls where the tire beads sit after the tire is installed and inflated.

Compare the tubeless optimized wheelset on the left with the classic clincher one on the right.

The channel is the key to getting your tires on. At that spot in your rim bed, while the wheel’s diameter is reduced a few millimeters, the circumference is reduced over 3x (or by Pi) more and that makes all the difference in getting your tires on your wheels.

Without using the channel, you probably won’t get your tires on. You’ll blister up your thumbs, abuse the rim beds and tape using tire levers, and likely swear till you are blue in the face.

So, use the channel and make it easy on yourself.

How? As you put the first sections of the first bead of the tire over the edge of your rim, put the bead into the rim channel and then mount the rest of that first bead into the channel as you go all the way around. Keeping that first bead in the channel, mount the second bead over the edge and into the same channel as go all the way around installing the second bead.

If you are having difficulty with the second bead, check to make sure that both sections of beads you already have mounted are still in the channel.

You also want to put the sections of each bead near the valve on last since the channel is blocked by the valve and the tire will sit higher there than if it were in the channel.

IRC created this graphic to show the steps.

Here are two videos that show some best practices for how to install modern tubeless road tires on tubeless-ready rims. They take slightly different approaches, but both work.

This one from ENVE starts with a tubeless road rim and shows you how to tape it and then inflate and seat it before injecting sealant. That’s the approach I follow.

This next one from GCN starts with a pre-taped tubeless road rim and shows how to use sealant before inflating to help you seat your tire bead. This approach works too.

In the next generation of wider wheelsets, we’ll also see more hookless rims. They are less expensive to make and improve aero performance slightly. At pressures typical of what you’d use for 23C and 25C wheels with 28mm tires (less than and probably, a good deal less than 80psi), the bead lock holds the tires in place without concern for the tires coming off the rim.

Emerging standards better define the rim diameter and tolerance for hooked and hookless rims at the bead lock. They also suggest a more current rim width to use in determining tire label sizes. This means that tires should fit more interchangeably with rims and measure truer to size once installed and inflated.

Unfortunately, we’re not there yet. While I hope installation becomes simpler and more uniform as the next round of tubeless wheels and rims are introduced, the current reality is that some tires mount, inflate, seal, and come off more easily on some rims than others. This is important not only when you put new tires on but even more so if you should have to install a tube on the road to deal with a major puncture that the sealant doesn’t fill.

For my tire ratings, I’ve noted which tires are easier or harder to get on and off the range of wheels we’ve tested.

What Matters Less

5. Puncture resistance – Of course, one of the main reasons to go tubeless is to protect yourself against punctures. When you puncture a tubeless road tire, the best measure is how quickly and well the sealant fills it.

This is puncture resilience, the ability of your tire to recover from a puncture.

On the other hand, puncture resistance, the ability of a tire to initially resist a puncture, is important if you have no recourse other than to get off your bike and replace your tube.

Puncture resistance is a throwback to the clincher world and matters much less in the tubeless one. Not only because of the role of tubeless sealant in filling the puncture but because tests run by BRR, Tour, and Wheel Energy show little difference in puncture resistance between everyday training and racing tubeless road tires with puncture belts.

By my lights, puncture resistance testing essentially evaluates the strength of your puncture belt and the thickness of your side walls. They don’t tell you anything about the puncture resilience of a sealant-filled tubeless tire.

A test that measured whether and how fast a tubeless bike tire resealed punctures of different sizes in the bottom and side of the tire spinning at cycling speeds would be more useful in choosing between them than the small differences in puncture resistance. Another test that evaluated the relative effectiveness of different sealants would be a bonus.

I don’t know how to do those tests but I’m sure or at least hope that some smart tire engineers will come up with something that tests tubeless tire puncture resilience rather than mere resistance.

The most important thing you can do to overcome the inevitable puncture is to make sure you’ve got the right amount of sealant in your tires or that you’ve got sealant at all.

Make sure to keep enough sealant (30ml) in your tubeless road tires for them to quickly seal after a puncture.

Of course, there are times when a puncture is so large that sealant won’t do the job. Usually, that only happens with a good-sized gash in the side or bottom of your tire or when you are racing on a tire with no puncture belt. For those situations, carrying a tube is still a good idea.

Using a set of all-season tubeless road or cross tires for commuting or on roads full of puncture rich obstacles will give you better puncture resistance than training and racing tires with puncture belts but will give you considerably poorer rolling resistance and road feel.

6. Weight – One of the arguments for tubeless road tires is that they weigh less than clinchers. As I mentioned above, this isn’t the case, at least not comparing today’s everyday tubeless tire set up, which includes sealant and tubeless valves and a clincher with a butyl tube.

Everyday training and racing tubeless road tires with puncture belts come in one of two forms. Tubeless TL tires have a butyl lining bonded into them and weigh, on average, about 290 grams. TLR tires don’t have the butyl lining and average around 260 grams. Add to that another 30 grams for the ounce (30ml) of sealant and another 5 grams for the mid-depth tubeless valve.

Altogether then, you are looking at about 325 grams for a TL tire, sealant, and valve and 295 grams for a TLR set up. (Note that some TL tires are labeled TLR).

As a reference, a top everyday clincher tire like the 25C Continental Grand Prix 5000S II weighs 215 grams. With a good butyl tube inside your Conti tire, you add about 75 grams, bringing the total to about 290 grams.

So, a top clincher and TLR setup are going to weigh essentially the same amount. No diff. A TL one will weigh 35 grams more. If you add 2 ounces of sealant instead of 1 (or 30 grams) as I recommend for 25mm tires, you’ll add another 30 grams.

While it might weigh on the minds of weight weenies, you’d be hard-pressed to tell these differences out on the road. That’s why I put weight in the matters less bucket of criteria.

Sure, if you want to go with a latex tube instead of a longer-lasting, higher-maintenance, less expensive butyl one, you can save another 30-40 grams per tire. Most roadies won’t.

7. Wear – The good news about riding different wheels and tires all the time is that I get to try out and evaluate a lot of new gear and report that out to you. The bad news is that I really don’t get to ride any one set of tires more than 1,000 miles.

Other than a tire that wears quickly or cuts easily within our testing period, I can’t really offer my own opinion on tire wear or whether one model lasts 2500 miles while another goes 4000 miles. Of course, we all ride on different roads, some of which are harder on tires than others so wear is personal thing anyway.

While I and most roadies I know are frugal and are always looking for a good deal, I will always pick a better performing tire over a longer lasting one that doesn’t perform as well. Spending $25 more per tire to get better performance or spending an extra $50 or so to replace better tires even twice as often shouldn’t be a budget-buster for most road cycling enthusiasts.

8. Price – Most better-performing training and racing tubeless road tires with protection belts have a market price between USD$50 and $60 per tire. One or two may sell for $15 less or $20 more depending on a current sale or from a particular store. But, compared to what we spend on our bikes, gear, apparel, food, event fees, etc., tires are a minor cost for such a big contributor to our performance and enjoyment on the bike.

With that in mind, I don’t let the price of tubeless road tires enter into my decision making criteria.

In The Know Cycling supports you by doing hours of independent and comparative evaluations to find and recommend the best road cycling gear and kit to improve your riding experience.

You can support the site and save yourself time and money when you buy through the links in the posts and at Know’s Shop to stores I rank among the best for their low prices and high customer satisfaction, some which pay a commission that helps cover our review and site costs.

Click here to read about who we are, what we do, and why.

* * * * *

Thank you for reading. Please let me know what you think of anything I’ve written or ask any questions you might have in the comment section below.

If you’ve gotten some value by reading this post or any of the reviews or comments on the site, click on the links and buy at the stores they take you to. You will save money and time while supporting the creation of independent and in-depth gear reviews at the same time.

If you prefer to buy at other stores, you can still support the site and new posts by taking a pull here or by buying anything through these links to eBay and Amazon. Thank you.

If you’d like to stay connected, use the popup form to get notified when new posts come out and click on the icons at the top or the links below to follow us on social media and RSS.

Thanks and enjoy your riding safely!

Interesting article which when I read it says more about the poor rollout of the technology from a PR standpoint, and the added effort necessary to set up tubeless wheels. Oh let’s also add the confusion caused by which tires work with which wheels (as your recent article addressed). If you look to cycling as a way to get 2-3 hours of exercise 3-4 times per week, I am not so sure any of this matters. So, is it a solution to a problem few have? Has the industry adequately made the point that this is in fact, the future? Seems not. I still think we are in the middle of this phase of change and where it will end up is not yet clear to anyone.

I have 2 bikes; a carbon and a Ti. When rolling on my Ti bike with carbon wheels and 700×25 tires, I often feel as though it’s the smoothest, most enjoyable ride one can enjoy. I typically flat 3-4 times per year using not too fancy tubes that I buy in bulk and can repair. Easy-peasy.

Tubeless for off-road, gravel, etc.? Definite maybe. Tubeless for road use? Not yet ready for prime time. I guess that puts me with the other Neanderthals at the right end of the curve.

You lost me after about three paragraphs honestly your montage about the topic is to long and boring.

Andy, Thanks for the feedback. Steve

That’s very harsh Andy. If you don’t want in-depth, honest reviews then don’t read Steve’s missives. They are always very in-depth covering every aspect of the subject. I really don’t understand why you read any of them, or participate if you think this one was too long and boring after three paragraphs.

Pete

Whow! Tsk!, Tsk!. Good thing you only lasted 3 paragraphs. Only means, this is not your Peloton.

Vic

OK friends, let’s move on. I welcome all voices but let’s focus on the content. Thanks, Steve

RE puncture resistance, I believe you will find that lower pressure equates to higher puncture resistance, which is yet another reason for tubeless. However I enjoy NOT having to mess with roadside repairs a whole lot more than the required tubeless setup it costs. The only roadside repair I have had since going tubeless was when someone dumped a box of box cutting blades on the tarmac and one cut the tire in half. Guess that would have sidelined a tubed tire as well.

And for many of us, who ride 6-7000 miles a year and puncture only maybe once in those miles, the ‘mess’ of a 5 minute tube replacement is really no big deal.

I’ve witnessed 4x mates running tubeless who have punctured, had sealant spray all over them, me and everyone else around before the puncture has either sealed with less than 30psi left in the tyre, or not sealed at all.

I’ve then seen them faff for nearly 30mins trying to plug holes with tyre worms, or remove a tubeless tyre and try to get a tube in, snapping tyre levers, not knowing how to use a tyre worm applicator properly and puncturing the rim tape etc etc. If they had been on tubed tyres they would have been on their way…

And of course, if they do unseat a tubeless tyre they they need to get it back on the beads – which takes a shot of CO2, which none of them seemed to be aware can affect many latex fluids and prevent them from sealing…..I could go on.

So until I see the following, I’m more than happy on clinchers with tubes;

1. Standard rim design.

2. Standard tyre bead design.

The above meaning all tyres can be fitted and removed from all tubeless rims without major effort.

3. A sealant that actually seals at road pressures as opposed to MTB pressures. (One of my above mentioned mates decided to top up his eventually sealed tubeless puncture at the cafe stop, only to blow the latex plug clean out and then had to start again!)

4. A sealant that is compatible with CO2 inflators so that once you have inflated a flat you don’t compromise another puncture sealing.

Because for all the supposed benefits, for the average leisure enthusiast (who is not actually racing) I simply don’t think that road tubeless is yet a game changer for me. Tubes, CO2, patches, are simple, proven, effective and fast to change. And with 1 puncture a year on average I’m more than happy to continue as is for now….

I totally agree Pete Smith. I was an early adopter of road tubeless and gave up a long time ago for the reasons you mention. Sealant that won’t seal at the high pressures, time wasted trying to fix a tubeless failure getting the sealant to work and then give up and put in a tube anyway. Something else you don’t mention which is a problem with all tubeless is tires is small sidewall punctures. No problem to put a boot and keep using until tire is worn out with conventional tire, but in tubeless, waste 10 minutes trying to see if it will seal, then have to run with a tube. Hate when the the sidewall puncture happens on the 2nd ride of $60 tire and now is essentially a tube tire for the rest of its life.

My experience exactly. Tried 3 different wheelsets. Setup was easy with all. However tried 8 different sealants with 3 different tyre brands. None sealed with the pressure I need for my 220 lbs. Just on big frustration. Plugs also don’t work.

Great article, I appreciate that you call out that there are so many variables that it is practically impossible to make any absolute statements. Throw in the individual factors such as each of our personal goals and preferences and it will always come down to a ‘works for me’ solution.

Personally, I have only been riding for a few years, but have typically been an early adopter. At the start of this year, I went all in on the aero bit. Even my water bottles are aero :-). I want to go faster and farther, and I’m willing to spend the money to do it. As part of that I tried the tubeless GP 5000’s.

What a freaking pain to get everything set up on my carbon rims. The idea of trying to add a tube, because the sealant didn’t seal (or seal well/fast enough and I lost a lot of psi), out on the road, 75miles in on long ride, in the heat, with a group waiting on you?- just no.

Now maybe it’s my rim/tire combination that is making it so difficult, but it’s not practical for the average cyclist to keep buying and trying with such expensive components. Then there’s the weight issue, my current combination of GP5000’s and a polyurethane tube is far lighter than the tubeless equivalent. And if the sites on rolling resistance are accurate (and I always believed these tests were more directional in nature) I’m ahead of the game on that as well. And given that your article accurately points out that aero is far more important than weight OR rolling resistance. What’s my motivation to deal with the tubeless hassle?

There’s a very good reason the vast majority of riders don’t glue on their tires like the pros, too much effort for too little gain.

I have weighed myself on the bike and have made psi adjustments. Measured wheels/tire widths to optimize aero and comfort, these measures cost little, with no downside.

This is not to say I have it all figured out, I’m saying that until there is some uniform commonality, it’s not something that will get many on the backside of your bell curve. Maybe the second or third generation will get us there.

Thanks for this article! Very well written and researched with great disclosure of the limitations. I’m past 70 and spend more time on my Peleton because I live in a place where we get in our cars to use our cell phones on roads that are ours alone but may be shared with others, who actually have no business using them. Sometimes I drive out of town to ride. At my age and (lack of) power (170 watts average over an hour) I don’t need the finest. On the other hand, if I find an excuse to pull out my TT bike, this article will have biblical influence. For daily riding I miss the ease of maintenance of my 1984 Bianchi. When I was racing it, I would disassemble it down to the last rear derailleur screw twice a year. The only thing I don’t miss is downtube shifters, though I could run up or down 4 gears and a chain ring one handed on the fly. My point: ease and low cost of maintenance trumps technology most of the time. Someday it would be nice if someone did a review of the easiest bikes and components to maintain that aren’t total slugs.

Fascinating article Steve. I enjoy cutting through the marketing to what really matters when it comes to technology, will it make your riding more enjoyable? So one thing you mentioned that really piqued my interest was the idea that you could run two different size tires. I am on 25C Conti 5000 but wondered whether swapping out the rear for a 28C might give me even more comfort without endangering myself! I realize this would mean that you couldn’t swap out the front and rears to even out the wear but if you aren’t comfortable you aren’t going to ride, so are there any negatives to running two different sizes on your bike?

Norbert, shouldn’t be a problem if you aren’t trying to get the best aero performance you can from the rear. Just make sure to set up your front and rear with the right tire pressure for each. If they are holding the same weight, you want to inflate a wider tire less than a narrower one. A bit more of your weight is in the rear so that’s why you often want to inflate the same width tire about 3-5psi more than the front. So with a wider tire in the rear where’s there’s more weight, you probably want to put it at close to same pressure as the narrower front. Use the Zipp tire pressure guide I linked to in the post to get a starting point and then lower both a few psi at a time from there until the handling gets less precise or a bit squishy. Then raise it up from there to where it’s good again. Steve

Excellent article and great comments by Pete Smith. I have been riding tubeless Mtb for close to 20 years and gravel tubeless for 3 years. I just converted my Tarmac SL-6 to tubeless after cutting a tire and needing to replace it. Conversion was a snap since I have had so much experience with TL, but now the comments Pete made have me wondering if road TL actually makes sense. I guess time will tell!

In all fairness to Andy’s comments, I can see how this article can lose its audience pretty early on. We all are cyclists at heart, however within this spectrum, some are stat oriented, whilst others want to just get on with it. We have been plagued with changes; tubeless, discs, carbon wheels, aero, lightness….list goes on. In my 35 years of riding, I have seen the greatest level of changes in the past decade. This has something to do with our ability to be socially more aware and connected with everything media related, in our case, GCN, Strava, youtube channels and the list goes on. We live in a world of apps. With that, we have speeds and feeds in real time of everything cycling related. Take the recent example of the Specialized Tarmac SL7 launch, which was straight of out the book of an Apple product launch, Tesla etc. The cycling industry is following other products and creating a hype. Whether it be these type of live launches, or through racing (aka Peter Sagan marketing). In my opinion I believe there are some merits to the underlying value . How much is that value ? To each it varies. It doesn’t take away from sticking to your tried and tested methods (steel bike, with clinchers and butyl tubes….proven). Whether we subscribe to any of these changes, is optional. I for one have resisted all the changes until a few years ago. Bought a carbon bike, then carbon rims, then latex tubes, then dropped $100 per tire and went tubeless, spent countless dollars on the tools needed to support the new tech. Where does it end. THe point is, we do have a choice, and its our own. Dis advantage, $$$$. Advantage, we are more passionate about cycling. This article for the right audience is that value proposition. Unfiltered . Ultimately, to the right person at the right time, will serve to be the value prop. I for one respect and appreciate the effort that goes into it. Well Done Sir.

great read. i’ve been riding on my shimano rs series wheels since 2015 and been holding off with tubeless after i’ve purchased my first set of carbon wheels. this in depth analysis makes me more comfortable with the switch. i’ve always said, if it’s not broken, don’t fix it and im comfortable with my clinchers. i guess it’ll be a last minute decision after purchasing the new wheels.

Regarding the Rule of 105 — are you saying that if the tire / rim combination violates that rule, then the depth and aero profile of the rims doesn’t have any aero advantage? If the tire is 100% of the rim or 95%, then the air will not re-attach and it doesn’t matter if the wheels are 40mm, 50mm, 60mm, or even deeper?

Oops, I said that backwards — if the rim is 100% or 95% of the tire . . .

Jim, When airflow diverts and doesn’t stick to rims when violating the rule, you lose the aero benefit of deep wheels on the leading edge of the front wheel, which is where more of the aero gains are made than any of the other edges of your wheels (trailing edge of front wheel and both edges of rear wheels). Steve

question….I’m approaching 3 months of rolling tubeless wheels, and it is time to check the level (Orange Endurance Sealant). If level is low, should I just add sealant, or is it better to dismount, clean all gunk out of the tire, and start fresh?

DMac, Unless the sealant no longer looks like it did when you put it in (watered down or separated, discolored, all-chunky), I’d just add to it. Steve

Like some here, I’ve been running tubeless for MTB for more than 10 years. I’ve done most varieties of tubeless setups (ghetto) back in the Dark Ages. Then cross, gravel and now road. In all of that time I’ve had 2 flats (1 MTB sidewall slash, 1 fat tire flat) that required a pushout home. Road tubeless overall has been great…kinda. On 650b x 47 tires I ran over a nail which punctured the front tire and stuck in the rear. I stopped, pulled out the nail and did the shake-and-bake with the sealant. Lost about 10 psi in both tires but rode another 50 miles no problem. BUT…the one problem which has happened consistently for me is after a noticeable road tire puncture, the tire will leak some sealant and air slowly at the site of the puncture when inflated to my desired psi. As others have suggested it seems that sealant etc works very well at lower pressures but maybe not as well at road psi. I’ve done bacon strip plugs and gorilla tape patches on the inside with suboptimal results. Given that I want to have confidence in my tires when going out for 3-5hr rides, I usually end up just buying a new tire. Anybody out there have experience or suggestions on how not to trash tires that would otherwise have many miles left in them?

I’ve just had my first go using road tubeless, on a sports-commuter rather than my racer. Using the Schwalbe 30mm Pro One TLE. Good news & bad – firstly the installation was easy as pie – easier than with tubes, they popped onto the rims without any air tanks etc, just a normal pump. The bad bit was losing pressure through the sidewall – to the point of actually bubbling under water dunked in the tub. But it wasn’t the valve/tape/rim interfaces that leaked but the actual tire sidewalls themselves. I poured in more sealant and after abut 4-5 days they must have sealed up the interior. The worse one is leaking from 45psi to 33 over 24h.

Ride wise I was disappointed since I read so many glowing reviews about tubeless suplesse etc. They do have a feel I would describe as “gummy” like riding with a shock absorber. I still don’t think they feel as good as high-thread count thin tread racing tyres with latex tubes. They are unrideably hard at usual pressure – I found a sweet spot at just under 45psi (70kg rider). Its not so much that they can be ridden at low pressures – they have to be. On the positive they do feel much more sure footed cornering however – they feel much less “baggy” at comfortable pressures.

Despite the pressure issue I am convinced I will keep using tubeless, its only one that is behaving especially leaky – maybe I got a bad unit. They also came is significantly undersized, under 29.5mm even on a 24mm wide rim. All in all there seem to be a lot of scare stories out there about how hard they are to install – I can confirm that’s all bunk.

Hi Greg, thanks for your input. While most tubeless tires these days are made with a bonded butyl inner liner that blocks air from leaking out the sidewalls, the Schwalbe tire isn’t. Initial set up including the right amount of sealant but also resting the wheel and tire on its side for 30 minutes or so and flipping it for another thirty minutes is a good way to seal up the sidewalls in addition to spinning it on its axis.

As to the ride, nothing rides like a high thread count thin tread racing tire (most which don’t have puncture belts). Also, you typically want to ride a tubeless tire 5-10psi below where you ride a clincher. 45psi sounds quite low for your weight unless you are riding on a pretty wide rim. If 24mm is your outside rim width, that’s way too low a tire pressure for a tire that width and your weight. It’s also far too wide a tire for good handling. If 24mm is your rim’s inside width, 45psi is still 5-10 psi below suggested levels for your weight.

Too low a pressure with a narrow rim/wide tire width discrepancy (light bulb shape) similar to what you described likely contributes to the baggy feeling and actually may not be very safe cornering at high speed. You could roll your tire. The tire inflation guideline charts I linked to in the post can help get you back to the right pressure. Steve

Thanks for taking the attention to reply. I do emphasise this is my commuter bike – im still riding on tubed 25mm Conti5Ks @75-80psi on my racer, although I usually ran my previous commuter wheels pretty low at 65 – the Zipp Course 30s – those lasted 3years of daily commuting with zero punctures. I wouldnt use such low pressure on a racing bike.

Yes I’ve done the lying then on the side treatment. The most pleasant surprise was just how well the (single layer) of tape & valve just work well to make the seal. No burps, fluid explosions or anything – I was put off for a long time by the scare stories.

After reading your other review I regret not having stuck with Zipp when moving to tubeless.

One of the funny experiences with tubeless is seeing how much the sealant slows down spin-down rotation – they look like they stop dead after 90secs compared to previously spinning almost 10mins. I wonder whether this is factored into all the rolling resistance tests that are so strongly touted in the advertising. Do you think they perform the tests dry or with fluid sloshing around?

Greg, All the different rolling resistance tests I’m familiar with use a motorized drum or pendulum and do use sealant or a tube (for comparison with clinchers). They are all over the map in their protocols but I’m not familiar with any that do spin downs. And I’m also not familiar with any wheelset or hubset that spins for almost 10 mins on a stand. Tell me more. Steve

I ride tubeless on one of my two sets of wheels. Two (same brand) had catastrophic blowouts on the front tire for no reason, let’s call it brand H. Thank God I wasn’t on a 50mph downhill, but even at 20mph, one of those was a bit hard to control. In each case, tread was fine on tire, and of course, no damage from abuse.

Let’s hope new tubeless brands, say brand M, have resolved this issue. I won’t ride brand H ever again.

Brilliant article, thank you. Really appreciated reading the answer to Greg’s question on air leakage from Schwalbe tyres. My 30mm G One speed leak air and require topping up every day ( a pain on multi day events) but comfort at 60 – 65psi is outstanding (I weigh 90kg plus kit) Only two punctures in two years requiring repair en route (big thorn and a flint) has made me a convert. My question though relates to a more relaxed winter set up and the 105 rule and loss of 5-15 watts – is it relevant if you are using mudguards or do the mudguards take off more wattage than a wider tyre?

David, I’ve not seen any testing on this but I’d guess that mudguards wouldn’t be very aero at all. Steve

I just got a set of Boyd 44mm clinchers. They have 19 internal and 27mm external. They recommended I get 28mm schwalbe one tle’s for the comfort factor. Am I giving up all aero advantages if the rims by doing this? Would I benefit from just outing a 23mm on the front and keeping a 28 on the rear? Also, is there somewhere that has a listing of actual widths of different tubeless tires? Looks like I would need an actual width of 25mm or less for a 27mm rim. Thanks for any advice.

Owen, Yes, depends on the tire, and here. Steve

Thanks for the response. I was wondering if the pirrelli p zero tlr 24c would work? It says that with a 19 internal it would blow up to 25. Also wondering about those enve ses that are 25 but are true to size at 19 internal. Failing those, I could go for the zip tangent 23. I’m assuming that wouldn’t blow over 25? Thanks again.

Owen, really hard to say without testing each combination. While some tires brands are running truer to size on 17 and 19c wheels, the hook design on the rim also matters a good deal too. And I haven’t tested the Boyd 44s as yet. Steve

Me again. I made a comment above.. It happened to me again a week ago. I got a nice puncture in my newish S works Turbo tubeless tire. Some sealant blew out and I lost pressure but reinflated to probably 60psi and rode another 50 miles home. But once home, when I inflated to 80 psi, the sealant wouldn’t hold. I tried a plug this time without success. This has been my experience with road tubeless. A puncture means you can maybe ride home without putting in a tube but the tire is trash. This has happened to 2 Turbos, a GP5000, and even a WTB Byway. The Byway held for a few rides at about 40 psi but then started leaking sealant during a ride. I like road tubeless but a new tire at $50-$80 per puncture isn’t worth it.

Winter layup of TL tires… does anything need to be done? With probably a 4 month winter layoff arriving soon in the Northeast, does anything need to be done to store my wheels/tires…such as removing the tubeless tires and cleaning out all the sealant?

Bike will be stored in the basement. Thanks.

DaveMac, In all good fun, the timing of your question is exquisitely bad and Karma crushing. It’s 70+ degrees where I live in the Northeast today and looks to be warm for the next week or so. And what good enthusiast takes a 4-month layoff because of a little cold weather? No, you don’t need to take your tires off and remove the sealant, but, if for no other reason than to remind you to put new sealant in after you get back on the bike next May, go ahead. Keep warm, Steve

Thanks Steve. BTW, I’m only 30 miles due north of you, and am all about the current 70 degree weather….and getting the miles in while I can.

Hey Steve- I’d written a while back about recommendations for a tubeless tire for my ENVE 4.5 ARs. I care about flat resistance and rolling resistance is secondary to that. I used to love the GP4000s but no go on the ARs. Last I’d written to you, think you had said the ENVE lineup that had then just released could work but you hadn’t tested them. Any thoughts on what to get?

Biren, We tested out the ENVE SES 25 tires and didn’t have much luck with them. I learned too late that they were a pre-production pair and ENVE made some changes since. So we’ll give the production 25mm and 29mm sizes a go in the spring. In the meantime, I’d suggest the Zipp RT28 a go if you want a great all-around tire or the Schwalbe Pro One TLE if you want a more aero tire. You can see the reviews and links to stores with the best prices here: https://intheknowcycling.com/best-tubeless-tires/#Reviews

Zipp Tangente RT25 have been my favorite tires. Ive tested Schwalbe, Vittoria, Continental, Mavic, and Hutchinson. I have Enve SES 5.6 and Bontrager Aeolus wheels and run them tubeless. The things I’ve learned with tubeless….(sigh). What i like about the Zipp is they are comfortable. I run around 70 to 75 PSI. I came to this thru my own testing. They mount up relatively easy. Id say less than 2 minutes without levers. I have a charger and it usually does the trick. I used the Silca Valves that came with the Enve wheels. Orange sealant works pretty well for me. They are pretty durable too. Thy seal up well. As with any tubeless if your spraying sealant every where you’re probably done for the day. Give them a try. It really cant hurt.

5 months and three slashed tyres later I’m back on Conti four season clinchers. Tubeless tyres are just not durable. One Hutchinson all seasons got a sidewall slash on the very first ride. I’ve had to put a new tube in to get home more often than I ever did with clinchers.

Hi Steve. Very good article, you certainly are thorough and seldom leave any relevant issue not addressed. However I think you in this instance have not given one downside of tubeless enough print.

I have been an “enthusiast” cyclist for 48 years, starting in my teens. I’m up in age now, a retired physical therapist, but still like to ride high end equipment as that what I’ve gotten use to. I ride alone almost all the time for several reasons, not least of which is the inconsideration shown to automobile operators when cyclist get into a group, at least the ones I’ve ridden with. It’s a two way street.

So riding alone I need to be self sufficient. I got some very nice B____ wheels, carbon tubeless for my Scott Foil Disc (latest bike). Not long after I got a flat, sidewall slash. The tires, Schwalbe Pro Ones had been mounted by the wheel manufacturer. I tried my best to remove the tires enough to place a tube which I always carry but no way was that happening. Long walk home. Once home I had to CUT the tire off. It was impossible to move from the bead seat due to the design of the rim. It’s fine to place the tire beads in the center depression of the rim when mounting the tire, but in trying to remove the tire you are starting at the full bead seat circumference of the wheel. I have tried Schwalbe, Hutchinson and Specialized tires (put them on with tubes) and only the Specialized could be removed and not cut off and that required myself and a good friend, a retired Navy machinist’s mate with very strong hands, working together. Took the wheels to two bike shops and the owner at one and chief mechanic at the other could not push the tire bead off the bead seat and into the rim center.

The problem for me is you can hardly find a wheel manufacturer any more that hasn’t jumped on the tubeless band wagon. I’m probably going to buy the Roval C 38 or CL 50 as they appear to have the older style rim cross section without the flat portion and small “hump” between the bead seat and the center channel. This allows just a small amount of moving the tire bead to the rim center to reach a point of smaller circumference of the rim. I’ve tried it with a Specialized bike at the dealer that came with the C 38 wheelset. Easy peasy.

Riders who prefer high quality carbon wheels used with tube and tire are being pushed out of that market. I think that’s a mistake. Most recreational riders need something that works reliably and can be fixed easily on the road. After having ridden tubeless prior to the sidewall slash puncture I just don’t see much difference. A few watts in the lab mean very little on the road. Your power level is your power level, it doesn’t increase if the machine becomes a bit more efficient. Maybe a pro or a few very serious riders who race can tell the difference but I would wager most enthusiast riders cannot. Regardless it’s not worth the maintenance headaches and the extreme difficulty of on road repairs. Allen C

6 months great then:

1 small (1mm..?) puncture front tyre

Would not seal permanently

Added new sealant twice

Still leaked some times fast others slow

Too much worry .. now tubed

Problem getting tubed tyre seated

Back tyre still tubeless but long nozzle tube in waiting..?

Make sure to check or top off your sealant every few months. 6 months is too long to ignore your tires.

I am soo tempted to go Bora Ultra WTO and conti 5000 tubeless but these stories deter me. Did tubeless once, several punctures in 3,000 kms the last one was a double puncture unseated rims and me nearly falling on incoming traffic. Ordered my first tubular rims and 50,000 kms later had 5-7 punctures, all but one sel sealing or sealable with mariposa or vittoria can. I only ride veloflex or Conti tubulars. at speeds from 35-70 km hr nothing would scare me more than a tubeless sudden decompression and waking up in a hospital as the witness testimonies mount, Why, because they are not standardized? now i am eager to jump to Conti tubeless and save watts, effort and gain comfort. but i feel them badly unsafe at least canada, vs tubulars. post winter we get too many chips and rocks and delaminating asphalt. Countless tubulars i retire at 2000-2400 kms (and i weight 80-84 kg with helmet and shoes!) they have several perforations of the casing BUT not the inner tube. Each one of those would have been a tubeless flat! and sprayed latex… so 6 controllable flats in 50,000 kms, vs near accident in 3000 km tubeless, i am sticking with safety, i ride 25-23 tires, with a new bike will do 28-25 tubulars, and hope that the tubeless ecosystem standardizes safely. Because bikes got faster, traffic speed fast with minor tailwind, 60-80 km downhill, so on. Sp riding fast, hard, tubeless to me is an unacceptable un standardized risk and gimmick. More comfortable. minutes faster over a 40-100 km, no doubt, but man these stories above make me reluctant… soo, i just do 40 km hr more tired… as for replacing tubulars, with mariposa tape it is a 10 min affair per rim, and i even repaired and reinstalled 2 of those flats, no issues.