HOW TO RIDE FASTER ON YOUR BIKE: 10 BETTER WAYS – GEAR AND KIT

Cycling enthusiasts want to ride faster on our bikes. It’s what makes us who we are. I’ve found there are 10 better ways to ride faster. In Part 1 I described the top 6 ways, all of which had to do with fitness or technique. In this post I’ll tell you about the next 4 ways. These are focused mostly on cycling gear and kit.

Here’s my list of the top 10 ways to ride faster on your road bike:

10. Don’t Make Yourself Slower

You can click on any of these and go straight to the description of each. Use the back button in your browser to return to this list. Or, you can read through the post to take them in order.

In The Know Cycling is ad-free, subscription-free, and reader-supported. If you want to help keep it rolling without any added cost to you, buy your gear and kit after clicking the store links on the site. When you do, we may earn an affiliate commission that will help me cover the expenses to create and publish our independent, comprehensive, and comparative reviews. Thank you, Steve. Learn more.

HOW TO RIDE FASTER TOP 10 – CONTINUED

OK, let’s jump back into our list with lucky number 7.

7. Get the Right Gear

Gear is seventh? Freaking number 7? Steve, you’re killing me! Are you nuts? How can gear not be near the top?

I hear you. Many enthusiasts think it’s all about the gear. The hype machine focuses a lot on the gear the pros use and less on how one rider is 2 kilos lighter than last year or how a second really improved his descending technique or how a third did some different training leading into the season to improve his position on the bike.

So, what you need to know is that most pros are already pretty good at the first five or six ways I’ve described to go faster on a bike and most road cycling enthusiasts aren’t. All things being equal, gear will make a big difference in going faster. But all things are not equal. If you are mentally, physically, and bike fit and have strong technique including knowing how to ride in a paceline and position yourself riding on your own, you’ll go faster than someone riding top-of-the-line gear but who doesn’t have the fitness and technique you have.

It’s when you are making good progress in your fitness and technique or taking it as far as your talents and time will let you that you’ll want to start getting better gear to ride faster.

This is where it gets interesting, controversial, quantifiable and, I think, exciting. Yes, doing a great interval training ride is something you can get psyched about and dropping 10 pounds coming into the season is something to be proud of. But, getting a new light bike or carbon wheelset or even some low rolling resistance tires can really get the adrenaline flowing.

So let’s dive in and pick out some gear to make you faster.

Weight vs. Aerodynamics

First, let’s deal with one of the most argued questions. Should I spend my money on lighter weight or more aero gear?

The simple answer is yes, spend it on both as both lighter weight and more aero gear will make you faster. The more nuanced answer is it depends on what kind of riding you are doing to know which to prioritize.

It’s at times confusing and maddening. So let me try to sort it out in a dispassionate way.

First, unlike pro cyclists, please recognize that road cycling enthusiasts are not full time, sponsored, young 20 or 30-something, world-class competitive riders who have only 6% body fat, ride 30,000 kilometers or 20,000 miles a year, average 42kph/26.5mph over the course of 5-hour 200K race, generate 5 to 6 watts per kilogram over a 1-hour maximum effort, employ veteran race tactics, get free gear, etc., etc.

Most of us enthusiasts ride around work and family commitments, are older, less skilled, heavier, don’t ride as much, as long, as fast or as powerfully, try to ride with our buddies rather than escape from them, and pay dearly for our gear. Our spouses? Not always happy with us. (See MAMIL on the right) But let’s hope we are better paid, better looking, and happier people. Or at least two out of those three. You pick.

As a starting point, both weight and aero as promoted by most bike companies have a much greater effect on separating out pro riders than it does enthusiasts. It benefits us for sure to ride with lighter, more aero components but it’s just one of the things that separate us. Ways 1 though 6 above matter more if you want to ride faster on your bike.

When weight matters most…

For the enthusiast rider, weight matters when you are doing long, steep climbs and when you are accelerating. It doesn’t matter when you are riding on the flats or rollers at a relatively steady speed. The more you, your bike, and whatever you are carrying on your bike (water, tools, tubes, pump, food) collectively weigh, the more energy and power you will need when you accelerate and when you climb.

If you are regularly climbing mile long, 7% or steeper pitches, you’ll benefit from lighter gear. But, lighter gear comes at a big cost relative to dropping a few of your own pounds or kilos.

As for gear, consider what added speed you can get going up one of those long 7% pitches if you jettisoned 4lbs/1.8kg off your bike by trading up from your current carbon frame to one of the new superlight climbing ones and by leaving off some of the extras you carry in your bag or back pocket. On this lighter bike, a 150lb/68kg to 160lb/73kg rider putting out an average of 200 to 250 watts would save about 10 seconds/mile or 6 seconds/km. That’s about 70 seconds faster up the famed Alpe d’huez (or it’s trainer equivalent, the Alpe du Zwift), a 6.8 mile/11 kilometer climb with an average gradient of 8.1%.

That same ride up the Alpe d’huez with a 300 gram lighter wheel, about the difference going from a stock wheel to a good all-around one or from that all-around to a climbing-specific tubular, would save you about 2 seconds/mile or about 15 seconds over the entire climb.

Those time savings are huge if you are racing. If you want to go faster up a climb in general and are willing to pay the money to get those weight savings, lighter weight gear can get you there.

Note that losing the same 4 or 5 lbs or 2 kilos from your gut would save you the same 85 seconds and cost you next to nothing. So do that too.

If you accelerate a lot following or are making moves in races or on group rides, weight also matters. Racers accelerate more frequently than enthusiasts, especially in short races like criteriums, to change the pace and drop riders.

When it comes to accelerating, wheelset weight is rotating weight and, according to physics, rotating weight takes twice the energy to accelerate as the weight on the bike that is static. So when you go to a lighter wheelset, if you save 150 grams it has the effect of saving approximately 300 grams elsewhere on the bike.

The weight of the rims, which typically makes up 60% to 70% of the wheels’ total weight, plays the most important role since it is both furthest from the center of rotation and makes up the biggest percentage of wheelset weight. Saving weight at the hubs with carbon flanges, aluminum hub bodies or ceramic bearings does next to nothing to improve your acceleration but can increase the wheelset price several times. (See Campagnolo Zonda vs. Eurus vs. Shamal Ultra. Fulcrum, Mavic, others do the same.)

Unfortunately, in the big picture, reducing the weight of your wheels, components or bike has a small relative benefit to saving the watts of energy you use when you accelerate. Why?

- You have to accelerate your own body weight plus all the weight of your bike. A 400 gram wheelset saving on a bike and rider that together weigh 80kg/175lbs is only 0.5% of the overall weight, 1% if you consider it all rotational weight. That results in about a 5 watt savings in the 500 watts you’d have to expend to accelerate out of a pack going 36kph/22mph to 54kph/34mph in about 10 seconds. (More on those numbers here)

- In addition to moving your total weight, you also have to overcome your added aerodynamic drag and rolling resistance when accelerating, each of which takes about an order of magnitude more force to overcome than the 400g difference in wheel weight. (More here)

While holding off a full discussion of aero and rolling resistance for a moment, it’s worth noting that a lot of the analysis behind weight and aero benefits is done on paper or in a wind tunnel rather than on the road. This drives road racing writers like Seth Davidson, aka The Wankmeister of Peloton Magazine, up the proverbial wall or perhaps a 25% grade in a Giro stage.

In his excellent piece, Does Weight Matter, Wanky points out that every couple of seconds or watts here and there make a huge difference to road racers when they are trying to make or follow moves during the course of a race. You find yourself 3 or 5 seconds back on a climb or on a flat and you are dropped. You have to expend a tremendous amount of energy getting back on.

Or, you can wait for the group that dropped you to come back to you. Fat chance. Without the group, you lose the benefit of drafting which makes it doubly hard physically and psychologically to get back on.

If you have to make up that kind of gap several times during a race, you are probably riding on the rivet before long. At some point, the pack is going to accelerate and if you can’t keep up, you’re done.

Does this translate to us as enthusiasts who don’t race much, if at all? If you are riding solo, a few seconds a mile on climbs or a few watts each time you accelerate out of a corner probably doesn’t matter unless you are comparing yourself against your personal best, targeting specific training times and power outputs, or competing against others on Strava.

Do a friendly group ride, however, and I think Wanky’s argument translates very well. I don’t know about you, but I feel like an absolute heel if I can’t keep up with my buds on a group ride. Not taking my share of pulls, getting towed along, or worse, having the group wait for me at the top of a hill or after we get stretched out makes me want to ride out in front of a bus sometimes. It certainly costs me a lot to pay for coffee or a round of beer for the group at the end of the ride.

Sure, it’s more likely that I need to train more or better or that the guys I’m riding with are stronger than me on a given day. But, when I just can’t keep up with my guys or in a paceline or a century ride, I’m looking for those few seconds and watts here and there to be able to hang with them until I can get myself in better shape, improve my technique or find the fountain of youth (still looking). If it gives me enough performance benefit to make a difference along with the psychological lift that comes with it, I want the lighter gear and I’ll find a way to pay for it.

When aerodynamics matters most…

Aerodynamics matter all the time, as I hope you took from my discussion on body positioning under #6 above. Aerodynamic gear – mostly bikes, wheels, and less so components – matter most when you are already going fast. Generally, you need to be averaging about 18 to 19mph or 30kph before you see a meaningful drag difference that translates to more than a few watts. And since the force needed to overpower your drag increases 3 times the increase in your velocity, the faster you go the more you need aerodynamic gear.

So, should you get a more aerodynamic bike or a lighter one? GCN looked at this question and concluded that there are some big-time savings you can get on an aero bike, but the choice between aero and lighter bikes isn’t as simple as which rides faster.

In their on-the-road testing, GCN found the aero bikes to be about 1.5% or 0.25mph/0.4kph faster than lightweight bikes while riding at 300 watts for 10 minutes on a road with varying terrain. Independently, Cervelo also found a 1.5% reduction in drag in their comparison here.

Over 40K/25miles, GCN calculated that it would result in a nearly full minute difference. I think it would probably be more like 30 seconds or so for most enthusiasts who can’t hold the speed that a 300-watt average output would generate over 25 miles and would lose the benefit of the higher reduction in drag at higher speeds. Nonetheless, even 30 seconds would be huge if you are into doing TTs or triathlons. If not, the relatively less comfortable aero bike might diminish the enjoyment of your time savings.

Here’s the video of the test GCN did:

Before you go out and buy an aero bike, however, consider that not all aero bikes are equally aero. The design of the bike and what wheels and components you put on it can make an aero bike no faster than a lightweight one.

To illustrate this point, consider the tests run by the German cycling magazine Tour. They ran comparisons of pairs of bikes – one aero and one lightweight – submitted by each of 12 leading manufacturers. Tour isolated the differences to the frames to a great extent by using common groupsets and wheels (Zipp 404 Fieldcrest). The tests simulated a 75kg/165lb rider doing 200 watts over a 100K/62mile ride with 2000 meters/6562 feet of elevation gain. This is more like the conditions of a fit enthusiast’s long solo training ride with a fair amount of climbing.

Tour found that, on average, aero bikes were indeed faster than lightweight ones. Also, the fastest aero bike in the test beat the slowest lightweight one by about 1% or 2 minutes and 30 seconds over the 100K ride. This would equate to 60 seconds over 40K/25miles.

The 1% in-the-lab test difference Tour found between the fastest aero and slowest lightweight bikes was in the same general vicinity as GCN’s on-the-road 1.5% finding, quite remarkable considering all the different test variables.

For example, GCN’s test used low profile wheels on the lightweight bike to minimize weight while the aero bike used pretty deep aero ones. Tour’s test used the same aero wheels on both. GCN used former pros on a short circuit with just two bikes. Tour used just the pedaling lower half of a robotic dummy across 24 different bikes. So the fact that the difference wasn’t any bigger than the 1.5% range convinces me that this is about the most benefit you get going to an aero bike.

What I find disconcerting though, was that the differences between the fastest and slowest aero bikes in the Tour test were about two minutes (1 minute 54 seconds) over the 100K simulated route. Remember the difference between the fastest aero bike and the slowest lightweight bike was only 2 minutes and 30 seconds.

Also, the biggest difference between an aero bike and the lightweight one from the same manufacturer was only 2:03. But, for 9 of the companies, their aero bike beat their lightweight one over the 100k/62miles Tour test by less than 1:15 minutes or about 0.5%. Surprisingly, in the case of two companies, their lightweight bikes actually beat their aero ones. Mon Dieu!

Further, Tours’ mechanical tests of rigidity and compliance showed the fastest aero bike was also the least stable and comfortable. Aero bikes are optimized to reduce drag by using flatter tubes that cut through the wind. Unfortunately, these tube shapes are less than ideal to improve rigidity and dampening.

So, if you already ride fast with big power output, you enjoy and are flexible enough to ride a race geometry bike, you are willing to trade off reduced stability (i.e., handling performance) and comfort for speed, you like to sprint at the end of a race to win by a wheel length, and you don’t plan to ride your bike in the mountains, then you will value the faster aero bike rather than a lightweight one. Just make sure to get one of the faster aero bikes, not just any aero bike or it won’t really matter.

(Are you getting my hint not to go for one of these aero bikes? Good.)

If you plan to do time trials and the occasional triathlon, then forget about the aero frame and get some aero bars to put on your lightweight or endurance bike. The way that aero bars move your arms in and torso down will save you a couple of minutes over 40K/25miles rather than taking 100K/62 miles that Tour’s test simulated to save you that same amount of time on their best aero frame. Going with aero bars is about 3x the benefit of going to an aero bike.

While Tour’s test showed that an aero bike, or really an aero frame, is marginally faster than a lightweight one, it also showed that putting aero wheels on a lightweight bike makes it nearly as fast as a bike with an aero frame and aero wheels.

So how much speed comes from aero wheels? And, what weight penalty do you pay for heavier aero wheels going up hills and when you accelerate?

These are much analyzed and debated questions. I think much of the debate comes from what is being tested and how the tests are done. Unless you are building your own bike or buying a $10,000 model, you usually can only buy a new bike with a set of basic, low profile alloy ‘stock’ wheels. It’s best then to compare aero wheels versus these alloy ones that you are replacing to see how much faster you’ll go by spending big on the new wheelset.

There have been many analyses and wind tunnel tests done over the years to establish the drag and watts absorbed by wheelsets of different depths and profiles (box, V, U and toroid) and at different angles to the wind (also known as yaw).

One of the most extensive and independent comparative tests on wheel aerodynamics was in 2007 by Roues Artisanales and remains the benchmark today.

As you can see in the chart above (click it to enlarge), a 2007 model year Mavic Ksyrium, Fulcrum Racing 7, Campy Hyperion or Citec 3000S stock wheel from that period absorbed about 30 to 33 watts of energy in the face of a 50kph/31mph wind at a weighted combination of angles to the wind that road cyclists are typically known to ride. Sadly, the rim profile and, assumedly aerodynamic performance of many of these (and most other) stock wheels have not changed much, and in many cases at all, since the time of these tests.

Compare the watt numbers of the stock alloy wheels to the Citex 6000, HED 3, Zipp 404, and other top performing aero wheels of that period. These circa 2007 aero wheels absorbed 19 to 21 watts, 11 to 12 watts less than the stock alloy ones.

Many new and more aero wheel models have been introduced since the time of this test. The aero profiles have improved by moving to a more rounded versus a V-shaped leading edge and with use by some of a toroid or bulb-shaped rim wall instead of one whose width remains the same or gets linearly wider as it approaches the brake track. The wheels have also gotten notably wider as measured across the opening between the brake tracks and the beads where the tire attaches.

Together these design changes have essentially increased the aero benefit of a mid-depth aero wheel like the latest generation Zipp 404 NSW over low-profile alloy stock wheels like the Fulcrum Racing 7 or Mavic Ksyrium SR by about half again, roughly to about 18 watts of difference at 45kph/28mph, an estimate I came to by triangulating a range of research I’ve reviewed.

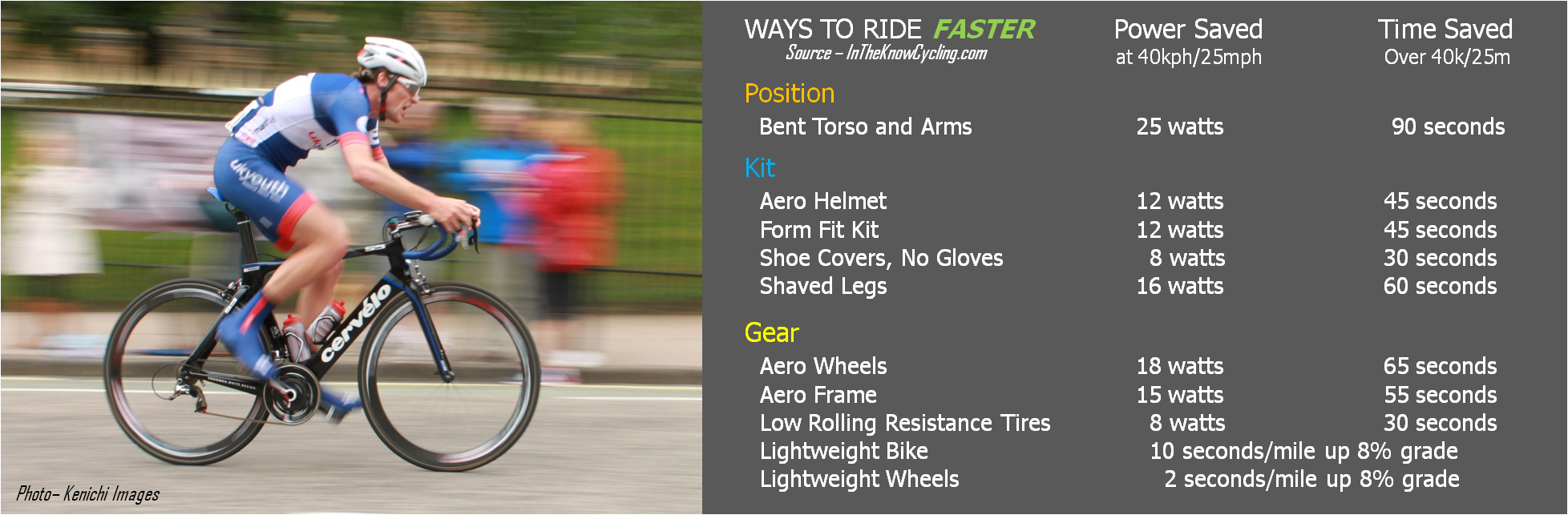

Over a 40K/25mile long distance, that 18 watts of savings will save you about 65 seconds of time.

Compare that 18 watt/65 second savings going to aero wheels to the 25 watt/90 second savings from optimally positioning yourself on the bike 50% of the time that I described before and you can see why we go ga-ga over aero wheels. That’s why upgrading from stock wheels to more aero wheels is such a high-value upgrade.

A few other things are important to note.

- There aren’t huge differences – a few watts, about a second every three kilometers/two miles – in aero performance between mid-depth (45mm to 60mm) wheels that roadies use and the deep dish (Zipp 808s and the like) that triathletes use. Enough for triathletes to justify it but not enough for road enthusiasts to worry about it, especially considering the disadvantages of handling the bigger wheels and their extra weight.

- There aren’t big differences between clincher and tubular aero wheel drag, though modern clincher tires (especially tubeless ones) have been shown to have lower rolling resistance than tubulars.

- There aren’t big differences in aero performance between the top brands or wheels of similar depth. See the chart below from ENVE of the testing done by Hambini.

While wheel makers will use every gram of drag difference to market their wheels one way or another, the important take away is that you should ride aero wheels if you want to go faster, but you don’t need to obsess on the relative aero merits of one brand vs. another. You should look instead at the whole package of benefits and drawbacks that come with a wheelset including its stiffness, comfort, handling, weight, price, how they appeal to you, etc. I consider 20 performance, design, quality, and cost factors in my criteria for recommending all-around wheelsets, which you can read here.

The acceleration benefit of a more aerodynamic wheelset is also notable. Using a similar scenario to that described earlier when looking at the acceleration benefits from lighter wheels – 80kg /175lb rider and bike, accelerating for 10 seconds, etc. – you can see in this analysis that more aero wheels produce about the same acceleration benefit as lighter wheels.

I say “about the same” knowing that the difference in this analysis and others I’ve seen usually favors the more aero wheel. The difference, however, is a matter of less than a wheel length, an amount that I think would be trumped by so many other variables (e.g. body position, power output, wind direction, kit fit) that the enthusiast couldn’t isolate a difference between the weight and aerodynamics designed into the wheel in the real world on the road.

Remember drafting has the biggest effect – 30% to 50% energy saved when you are riding in a group. When you are getting those drafting benefits, you don’t get the full aero benefit you do when riding alone in the wind. If you ride in a paceline all the time, you get maybe half to two-thirds of the aero benefits from your gear compared to what you would get riding alone in the wind.

The important thing is that, compared to the stock wheels that likely came with your bike, you can both reduce your wheel weight and improve your aerodynamics with an all-around, 45mm to 60mm carbon wheelset. I don’t really see the reason for this weight vs. aero argument to continue when you can have your cake and eat it too as far as going faster is concerned, assuming you can afford the cake and will burn off the calories from it in your training.

When tires matter most…

In this unnecessary weight vs. aero debate, a discussion of tires is usually left out. This is a huge mistake. Tires create rolling resistance that takes power to overcome. Tires also have a shape that plays a part in your wheels’ aerodynamic performance. Finally, tires and tubes add weight that contributes to your rotational mass.

All of these, roughly in diminishing order of importance, play a role in how to ride faster on your bike.

Different brands, tire widths, and tire pressures you select will create more or less rolling resistance, better or worse aerodynamics, and more or less weight.

– This section goes into the theory and results detailing what I’ve tried to simply state above. It gets quite involved. If you don’t want to wade through it with me, I understand and won’t be hurt. Instead, just go out and get a pair of Continental Grand Prix 5000 tubed tires (compare prices here) or 5000 TL tubeless tires (here and here) in the 23C/23mm size or 25C/25mm size (the 25s only if you have wheels that are 27mm or wider at the brake track) and you’ll go about as fast or faster than on any other set of tires.

If you want to know why I and a lot of other people pick that tire or you think you should get another brand (like a Michelin or Vittoria) or another type of tire (like a tubular) or even a wider size tire (like the 28C or 32C) on whatever width wheels you have because it’s what everyone seems to be doing these days, keep reading. I’ll try to explain the tradeoffs and speed gains and losses from different tire designs and models in language enthusiasts can understand.

Warning, it does get a little thick at times.

But, I won’t talk about tire weight any further. It makes an almost insignificant difference in your choice of tires and I’ve already written about weight’s effect on speed earlier. Tube weight matters, not tire weight, but not because of the lighter weight. It just turns out that a lighter weight tube provides better rolling resistance.

Are you with me? OK. Here we go. First, some more background.

Rolling resistance is caused by the friction created within the materials that make up the tire, the amount of deformation of the tire over time (aka hysteresis), and the energy of the tire leaving and coming back into contact with the road surface. The more friction, hysteresis, and on/off contact with the road, the greater the amount of tire rolling resistance.

A tire that is suppler or more flexible, often because of the higher fiber thread count and more elastic compound used in the tire will create less friction and less rolling resistance than one that has a less flexible casing. Using a thin butyl tube or a harder to find (and probably more trouble than it’s worth) latex tube inside a clincher tire instead of the more common, thicker, and more puncture-resistant butyl tube used by most enthusiasts today will also reduce rolling resistance.

Tom Anhalt writes the Blather ‘bout Bikes blog and has published reams of data comparing various tire models over many years. His tests show that tires with the least rolling resistance can save you 5 to 10 watts at 40kph/25mph or about 20 seconds over 40K/25miles compared to similar construction tires. You can also save another 5 to 8 watts using a latex tube versus a butyl one at 40kph.

The best clincher tires today have about the same rolling resistance as the best tubular ones. Tubulars don’t give you a rolling resistance advantage. Bicycle Rolling Resistance, another independent tire testing site, has found that the best tubeless tires have slightly lower rolling resistance than tubed clinchers.

Three huge caveats:

1) Some of the tires with the lowest rolling resistance have very high thread counts, very high prices, and don’t last as long as your typical everyday training tires. Take them out for races only if you race. There are everyday tires that come in only a few watts away. The enthusiast should go for those.

2) Latex tubes can be quite expensive, are less durable on the road, need to be topped off with air every day, and don’t store well in varying temperatures. These issues make them less practical, harder to find, and probably suitable only for racers. Don’t expect to leave one in your saddlebag for months and expect it to be ready to rock when you need it. The best option is to go with a light butyl rubber inner tube for fast riding and a heavy butyl one for training. The light or thinner butyl tube will probably save you about 2-4 watts over a heavy one.

3) The biggest caveat is that rolling resistance is only part of the equation in figuring the relative speed benefit one tire gives you over another. Aerodynamics is the other. What normally improves rolling resistance worsens your aerodynamics. They don’t have a totally predictable relationship. Stay with me. We’ll get into that a little further down in this section.

Let’s look next at the effect of tire width and inflation pressure on rolling resistance.

At the same tire pressure, a wider tire will have more of the tire’s width and less of its length in contact with the road than a narrower one. This wider ‘contact patch’ will create less longitudinal deformation and therefore less rolling resistance. The benefit of the wider tire diminishes as you get incrementally wider. Going from a 19mm to a 20mm wide tire can save 1 watt, shifting from 23mm to 25mm tire saves less than half a watt. So while there’s a real handling benefit going to a wider contact patch and there is an aerodynamic effect which I’ll discuss later, there’s not a big rolling resistance benefit going to a wider tire.

The effect on rolling resistance at different tire pressures depends on the surface you are riding. On a relatively smooth road surface like those most road cycling enthusiasts ride most of the time, a more inflated tire will create a smaller contact patch, the added pressure supporting more of your weight than a less inflated tire would, and you’ll move down the road with less rolling resistance.

On a bumpier road like those off-road paths and trails ridden by gravel, cyclocross, and mountain bike riders, the unevenness of the road will cause a more inflated tire to leave and come back in contact with the trail more frequently than a less inflated tire, creating more rolling resistance for that more inflated tire than on a smooth road. The less inflated tire, despite increasing its rolling resistance from a bigger and longer tire patch needed to support your weight, will have less additional rolling resistance on an uneven road than will a more inflated tire because the former tire will lose contact with the rough road or trail surface less frequently than the later will.

Relatively speaking then, a more supple, wider, and more inflated tire will provide less rolling resistance than a less flexible, narrower, and less inflated one on the surfaces that most road cycling enthusiasts ride.

How many watts difference do tire width and inflation make on rolling resistance and how rough a road is needed for you to want to lower your pressure below what you normally would to improve your rolling resistance?

A series of rolling resistance tests performed by an independent lab for VeloNews (here) shed some light on these questions. They compared different widths or two models of tubular tires with similar casings (or suppleness) and different tread patterns. Each width tire was also tested at different inflation pressures. The tires rolled up against a drum whose surface texture simulated what would be a relatively rough road surface for road cyclists, one with cracks or made of a combination of asphalt and fine aggregate commonly known as ‘chip seal’.

The results showed that width and inflation pressure differences have a pretty small effect on rolling resistance within the range of variables and conditions most enthusiasts ride. The rolling resistance at 40kph/25mph for one model of tires was about 3 watts less for the 24mm wide size than the 22mm version. A second model of tires showed about 1.5 watts less rolling resistance for its 25mm wide size compared to the 24mm one.

Even on the rough road surface this test simulated, the tires inflated at 112 psi had less rolling resistance than the ones inflated at 84 psi by 0.1 to 0.3 watts for tires of the first model and by 0.5 to 1.5 watts for the tires of the second model.

The two models had different tread patterns but the results show they didn’t alter the conclusion you can take from these tests.

If you came of riding age like me when narrow, hard, 120psi tires were the manly thing to ride, and because you thought that those characteristics put the least amount of tire in contact with the road, we were partly wrong as far as minimizing rolling resistance. Now, most of us want a wider tire with lower pressure for better comfort and handling. That combination doesn’t provide the least rolling resistance either.

I’m a firm believer that handling and comfort come first, especially if I’m going to stay confident and energized over the course of a long ride. I want the right width and inflation that is best to meet these objectives, rolling resistance differences be damned. Taken together, the width and tire pressure differences in the VeloNews commissioned tests varied at the extremes (wider/more inflated vs. narrower/less inflated) by only about 2 to 3 watts. So what you see is that you aren’t penalized or benefited greatly (a few watts at the extremes) by picking the width and inflation pressures that you prefer.

This chart shows the recommended pressure for your weight and tire width. These are good guides or perhaps starting points in finding your most confident and comfortable inflation levels.

Unfortunately, you cannot look at tire rolling resistance and aerodynamics independently. They must be considered together and in light of the width of your rims.

The first thing to note is that narrower tires are usually more aerodynamic than wider ones. This makes intuitive sense since narrower tires have less rubber going into the wind.

Rims on alloy stock wheels and the most popular alloy upgrade wheels these days are 21mm to 23mm wide at the brake track or where the tire meets the rim. For these types of wheels, 23C or what’s often labeled 23mm wide tires will typically be the most aerodynamic choice. However, stock and alloy wheels are almost always less than 35mm deep and typically no deeper than 25mm. Therefore these wheels are not aerodynamic in the first place and you are better off running 25C wide tires on them for the comfort and handling benefit those wider tires provide.

Modern carbon wheels typically run 25mm to 28mm wide and at least 40mm deep. This is a depth at which their aerodynamics can provide you savings if you are going at aero speeds (>18mph/29kph) and getting the right width tire will provide you further aero performance.

In almost all cases, this means getting a 25C or 25mm wide tire.

I say “in almost all cases” because not all 25C tires measure the same once mounted and inflated on your rim. Tires with the same C designation can vary in width by 1-2 mm. They will also vary once installed based on the inside width of your rim which itself can vary from 17mm to 19mm to even 21mm for a similar outside width.

I’ve provided more detailed explanations of this in this Know’s Notes post.

The most aerodynamic tire is one whose sidewall continues the width and shape of the rim at and beyond where they intersect each other. The airflow will be more disrupted and therefore less aero the greater the difference in width between the rim and tire.

A tire that is considerably wider than the rim will also create a less aero ‘light-bulb’ shape. Air will travel more smoothly, staying attached longer to the rim-tire combination if the widths are closer and the tire’s sidewall is more vertical than bulbous.

Several years ago, FLO Cycling actually measured the aerodynamic drag of their 24mm wide FLO 30 front wheel with four leading tires. Here’s the graph of the results:

Interestingly, the width of the tires used on the FLO 30 rim for this test, in order of most aerodynamic to least were 24.2 (Continental 23C), 23.0 (Bontrager 22C), 23.3 (Michelin 23C), and 21.5 (Vittoria 22C). I don’t think it’s a coincidence that these tire widths mounted on this 24mm width rim align with their combined aero performance. I also don’t doubt the tire’s performance order would be flipped if these same tires were on a 21mm rim like a Shimano Dura-Ace C40.

What’s the wattage difference? At the 48kph/30mph speed tested, the differences between the four tires tested varied from 0 to about 2.5 watts at the range of yaw or angles to the wind where road cyclists ride most of the time (Mavic’s Ponderation law).

Most of what represents the modern generation of carbon wheels were designed for 25C tires. Pick the wrong 25C however and you’ll lose a few watts. Pick a 28C tire and you’ll lose even more.

Josh Poertner, Zipp’s lead engineer during the Fieldcrest aero wheelset development period established what he called the Rule of 105. It says that “the rim must be at least 105% the width of the tire if you have any chance of re-capturing airflow from the tire and controlling it or smoothing it.”

It’s hard to tell whether the improved rolling resistance of a wider tire outweighs the increased drag it brings on. Rolling resistance probably matters more in road racing where the aero benefit is reduced by the amount of time riders spend drafting and staying out of the wind.

If you are training or doing events where you are in the wind a lot (i.e., riding without a draft or at the front of a paceline), it may be more of a balance or favor aero. And, if you lower the pressure of your wider tires below what you run your narrower ones at (and the Michelin Man says you should), you increase the size of the tire patch, eliminating some of the benefits of the wider tire’s lower rolling resistance.

I don’t know about you, but it seems a bit crazy to me to buy a new set of wheels and then put a tire on it that promptly defeats some of the aero benefits you just spent good money on.

From what I’ve learned doing the research for this article, my approach going forward is to pick a few tires with the lowest rolling resistance I can afford and then select the one whose actual width is as close to the brake track width of the rims I’m riding (or front rim if the rim widths are different). For my review of tubeless tires, I measured the tire and brake track widths for a range of tire/rim combinations.

If I’m in more of a comfort than speed mood on a given day, I can lower the tire pressure a little. I can always pump it up on days I’m targeting more speed.

Bottom line – between rolling resistance, aerodynamics, and my knowledge of which tires to pick for my rims and how best to inflate them to get the right mix of speed, comfort, and handling I want, I figure I’m going to save myself 5-10 watts of power or 20-40 seconds over 40K/25miles at the speeds I normally ride.

That’s why tires should be a big part of the discussion if you want to go faster on your bike.

8. Suit up for Speed

Maybe your mom used to pick out your clothes when you were younger. Perhaps you played sports and had to wear the same uniform as everyone on the team right down to the socks. You started working and there was an explicit or implicit code outlining what you should and shouldn’t wear. Or you just felt the pressure to wear what was within the norms of style, taste, maybe even hip. Maybe you’re a jeans and a t-shirt kind of guy. Well, that’s a uniform of sorts too.

Cycling is a release from all of that for many of us. Express yourself with your choice and color of bike and kit, your selection of components, where you ride, who you ride with, what events you do. No two cyclists are the same. You are an individual! Vive la difference.

Well, I’m going to tell you that, if you want to ride faster on your bike, you’re going to have to conform to a cycling dress code of sorts. But unlike the restraints you may have felt with school or work clothes, this dress code is going to allow you to literally break free of the pack and every non-conforming cyclist too dumb not to realize how much faster they can go with these easy and inexpensive ways to suit up for speed.

Here’s what the fast kids wear – from head to toe – to go faster.

Helmets

Helmets have come a long way in a few short years. There were time trial helmets, those long, unvented pointy things only the pros and way-to-serious amateurs used. Roadies wore the ‘bowls with holes’ to maximize airflow and cooling across our lids. For a while, it seemed aero helmets that skirted the wind and standard helmets that attracted it were in entirely different orbits.

Fast forward to today and you’ve got helmets that are both aero and cool if not totally hip, though some are all three. Better yet, for the road enthusiast looking to ride faster, you can reduce your time over a 40K/25mile distance by between 30 and 60 seconds (10-15 watts) compared to the standard heavily vented helmets your currently wear. The performance of these new aero road helmets looks to be about 2/3rds the benefit of the full-on reverse peacock beaked lid with most of the cooling you get from a standard road helmet.

At $250/£150/€200/AU$300 for the best of them, it’s not free speed but probably amongst the cheapest speed you will find.

These aero road helmets started showing up for us enthusiasts in 2014 and there several models to choose from. I’ve tested more than a dozen of them over the years and the best are compared in this review.

Kit

The fit of your kit can produce massive benefits in speed if you haven’t paid much attention to them in the past. Specialized ran the wind tunnel test you see below of warm and cool weather kits that were either loose or form-fitting.

At a wind speed of 50kph/31mph, the form-fitting kits saved between 80-90 seconds over a 40K/25mile distance. I’m not sure I buy that – it’s the same amount of savings as putting your body in an aero position with your arms and torso bent while your hands are in the hoods or dropped. But even if it’s half of that, it’s massive and also inexpensive compared to other gear you can spend your money on.

If you aren’t too embarrassed with your shape, getting a few kits that fit you snug for those rides you want to go extra fast will do it. If you aren’t as trim as you want to be just yet, the time savings you’ll get when you buy some new jerseys should be another great motivator to lose the weight.

Glove your shoes and shoo your gloves. Yeah, I just wanted to write something cutesy/clever just once in my pitiful blogging career. In reality, the straps on your bike shoes create unnecessary aerodynamic turbulence. Shoe covers smooth the airflow.

Padded gloves with Velcro straps across the top are not very aerodynamic either. Most fast cyclists don’t wear them.

With a good bar tape, you really don’t need the padding in gloves anymore. If your arms and hands sweat a lot, you may find gloves to be good for gripping the hoods and keeping the sweat out away from your shifters. If so, get the thinnest gloves you can find and ones that extend over your wrists.

Data and estimates vary over how much savings is to be had from losing the gloves and adding the covers. From what I’ve seen, it could be another 30 seconds over 40K/25miles. Another simple, inexpensive way to get faster.

Shave your legs. Tradition says to do it but is it really faster? Yes! Depending on how hairy your legs are (what Specialized calls the “Chubaka Scale”), you can save between 50 and 80 seconds over 40K according to what was probably the funniest edition of the Win Tunnel. Watch below.

This is probably the easiest and cheapest way to go faster on your bike. Get in touch with your feminine side unless, of course, you are a woman in which case you are likely already shaving your legs. Men, if you want to compensate elsewhere, know that growing a beard won’t slow you down any!

And because I know someone will likely ask, if you are riding with only one water bottle, put it on your downtube rather than your seat tube to be more aerodynamic.

Note: Many of the tests I’ve quoted use either 40kph/25mph or faster speeds for 40K/25 miles for their tests. I know most of us ride slower so these time savings will be less, right? Actually, while you will finish later, you’ll actually save more time over the same distance if you ride slower despite the fact that aerodynamics improve exponentially with speed. And if you ride longer – centuries, fondos, sportives, audax, and the like, you’re looking at more than 4x the time saved I’ve been quoting here. Yeah. Really. Zoom Zoom.

Here’s a good video explanation of why you save more time going slower.

9. Maintain Your Gear

Getting the right gear to help us ride faster is a huge focus. Unfortunately, maintaining it is not. That can cost you time on the road, the time you spent dearly to achieve with the new gear.

Fortunately, maintaining your gear isn’t hard even if it does take a few minutes in the basement or garage every now and then. Think of it as another important part of your training discipline. Do it regularly and you’ll enable yourself to go faster and get as much as you can out of your gear.

Maintaining your gear is actually quite simple and inexpensive. You don’t need to be a mechanic or even terribly handy around the house to qualify. Here are the basics.

- Regularly clean and lubricate your chain – a dirty or dry chain, beyond wearing your chainrings and cogs faster than normal, makes for inefficient shifting and that slows you down. To maintain your speed, simply clean off your chain after every ride and lube and wipe it after every few rides.

- Periodically clean and lube your bike thoroughly – Every few months or after a particularly wet or gritty ride, you’ll want to thoroughly clean your entire bike. This is an opportunity to degrease the chain and derailleurs, get the gunk out of your brakes, remove the dirt stuck to the bottom of your downtube, and generally get it humming again. A clean and re-lubed bike is not only good for the bike, but it’s also good for your morale as well. Here’s a great video to take you through an entire wash and lube in 30 minutes.

- Adjust or replace your shift and brake cables – Just as a dirty chain makes for inefficient shifting, stretched or worn shifter cables will do the same. Either of these situations may cause you to take longer to execute a shift or subconsciously avoid a shift altogether if you think it won’t be quick or smooth. Riders who have moved over to electronic shifting report the added precision and confidence some feel cause them to shift more frequently and more closely maintain the cadence they want. This will ultimately make you faster, or at least use your energy more efficiently and save some for when you want it rather than when you need it to recover from a bad shift.

As for brake cables, bad brake adjustment, cables or pads may cause you to brake harder than you need to go into turns, making you that much slower and using more energy to come out of them. Riders using disc brakes on their road bikes can go faster into turns and down hills with the confidence of the superior brake feel and control they have.

Adjusting your shifter and brake cables is usually pretty easily done by turning a barrel adjuster; replacing them is a bit more of a job. Four videos are worth a look here.

While most of the adjusting can and ideally should be done before you head out for your ride, you might find yourself wanting to do so on the road during a ride. Check out these two videos for how to do the simple and on the road shifter adjustment (here) and brake adjustment (here).

For a video on replacing your shifter cables click here; for one on replacing your brake cable click here.

- Inflate your tires properly – I wrote a too long section above about setting your tire pressure where you want it to get the right balance of speed, handling, and comfort for your rim size and weight. There’s little I hate more than taking a couple of minutes to check my tire pressure when it’s the last thing holding me back from getting out on a ride. But, it’s worth it. If you are a couple of psi off one way or the other, the next several hours on your bike could be slower or less comfortable than you want.

- Calibrate your power meter – If your power meter doesn’t calibrate for temperature automatically, take a minute before you start to do it. There’s nothing worse than being unsure about whether the big numbers you are putting up are overstated or the low ones you are seeing are a sign that you are washed up.

- Massage your legs and more – While not exactly gear, your muscles need to be maintained as well as your gear if you want to ride faster on your bike. If you can’t afford a regular visit to a masseuse (ha), you can regularly use a $25 roller along your own momentum to do the massaging. Here’s a good guide to using a roller courtesy of RideOn Magazine.

Maintaining your bike, and the speed increase that comes with it is pretty easy.

If you want to go further and release your inner bike wrench, check out my best bike repair stories on getting the right tools and setting up a shop to work on your bike. Once you get proficient, you can save yourself some serious time and money. If you’ve already got the basics down, here are links to YouTube video libraries from Art’s Cyclery, Park Tool, and GCN that will show you how to do most anything.

10. Don’t Make Yourself Slower

After all the work and money you’ve put into riding faster, the last thing you want to do is something that’s going to make you slower. Seems obvious, right? But there are some things we busy road cycling enthusiasts do all the time that slow us down.

The holy trinity of athletic performance improvement is TRAIN – SLEEP – EAT. Without getting all three working together, we limit how fast we can go on the bike.

For most normal adults 7 ½ to 8 hours of sleep is optimal before riding. If you are training hard, this is a critical time for your body to recover and for your muscles to repair and grow.

I know, I know, you aren’t normal and don’t need that much sleep. Don’t have time for it either.

Perhaps so, but you are only slowing yourself down my friend. Try getting more sleep before a long weekend ride. Go to bed a half-hour earlier on weeknights. See if it makes a difference (it should). You are the one that wants to ride faster. I’m just telling you to do that and how not to ride slower. Not getting enough sleep will make you slower.

As to eating, we can be our own worst enemies. Maybe you can’t eat as well as I described under 5. Drop/Hold the Weight by getting the right combination of protein, carbs, fruits, and veggies with enough water to make you pee throughout the day. But don’t, I repeat DON’T think that since you ride all the time you can eat whatever you want and whenever you want.

Eating the wrong stuff at the wrong times will slow you down. Dairy for breakfast before you go out for a long ride? Bad idea. Overeating the night before a long ride? Congrats, you’ve just added a couple of pounds to carry up the hills.

Even if you can’t always be eating the right things, you can certainly be smart enough not to eat the wrong things or eat at the wrong times or eat the wrong amounts. If you do, it will slow you down, plain and simple.

If you jumped into the discussion about how to ride faster with this post, be sure to check out Part 1 of How To Ride Faster On Your Bike: 10 Better Ways that focuses on the training and technique we enthusiasts use to get extra speed.

Find what you’re looking for at In The Know Cycling’s Know’s Shop

- Compare prices on in-stock cycling gear at 15 of my top-ranked stores

- Choose from over 75,000 bikes, wheels, components, clothing, electronics, and other kit

- Save money and time while supporting this site when you buy at the store after clicking on a link*

*While there’s no added cost to you, some stores pay commissions that support our product review and site expenses.

* * * * *

Thank you for reading. Please let me know what you think of anything I’ve written or ask any questions you might have in the comment section below.

If you’ve benefited from reading this review and want to keep new ones coming, buy your gear and kit after clicking the store links in this review and others across the site. When you do, we may earn an affiliate commission that will help me cover the expenses to create and publish more ad-free, subscription-free, and reader-supported reviews that are independent, comprehensive, and comparative.

If you prefer to buy at other stores, you can still support the site by contributing here or by buying anything through these links to eBay and Amazon.

You can use the popup form or the one at the bottom of the sidebar to get notified when new posts come out. To see what gear and kit we’re testing or have just reviewed, follow us by clicking on the links below or the icons at the top of the page to go to our Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and RSS pages.

Thanks and enjoy your rides safely! Cheers, Steve

Follow us on facebook.com/itkcycling | twitter.com/ITKCycling | instagram.com/itkcycling

Nice post 🙂 Been trying to lose that 5 lbs for 2 months. It’s not happening. Yet.

perhaps try the HIIT cycling method ? ( i have just started doing this. i had already lost some 16 kgs last year since i started cycling ( in march, done about 11000 km since )

reading all my timings , i learn’t that i have stagnated in the past couple months and am not going any faster. so i googled training plans and HIIT came up regularly ( high intensity interval training ) i am not doing it to lose weight, but to simply get stronger and faster. but i do hear that it burns fat a lot lot more than just cycling regularly ( and in less time)

good luck 🙂 ride safe

Great post. There are so many focusing on gear when they really should get (more) fit. I recommend a pre breakfast ride. Have been working great for me by commuting to work, lost 4-5kg since march. That’s half the weight of a bike?

Thanks for another great post. One thing that seems like it should be important but don’t see addressed in any detail is chain lube. And after hunting around on the web, I’m totally confused. In fact, in an accompanying video to the one above on bike cleaning, the presenter recommends WD-40… just the opposite of what I’ve read elsewhere. I’d sure appreciate some well considered advice.

rkman, thanks for your comment. Yes, I’ve seen him talk about WD-40 but I wouldn’t use it personally. It’s a degreaser rather than a lubricant. Cleans the chain but doesn’t lube it. I’ve had good luck with Boeshield T-9. Steve

Good afternoon Steve,

I always appreciate the great advice in your articles!! Regarding kits, you suggest losing the gloves and covering the shoes for aerodynamic benefits, and that makes perfect sense. However, I am having difficulty with hand numbing. Have been making adjustments with my bars and seat to improve things (making some but slow progress) and wondered if a padded glove would help until I get my fit all sorted out. In your picture you are wearing gloves and just wondered if you had any suggestion on best glove choice?

Core strength is part of my issue but it will probably take a while before my exercises pay off. 🙂

I am 6’3, 160 pounds and 63 years old.

I have a professional bike fit scheduled on May 9th. This should help. The physical therapist doing my fit is associated with our local hospital, is an avid biker and is credentialed as a Serotta International Cycling Institute Certified Fitter. I don’t know if that is a quality bike fit method, and would like your insight on the certification. My LBS gives “free” bike fit advice, but does not do a complete bike fit.

Thank you!

Wheldon, A good fit may address your hand numbness and I’d wear gloves until you get that done. Once fit, if you still have the problem, appropriate tire pressure (maybe 5 psi lower than appropriate), better bar tape, wider tires on the right size wheelset would be the things I’d try roughly in that order. If gloves also help, stay with them. I’d rather be comfortable and a tiny bit slower than numb. As far as the fitter, I know several good fitters including my own who have the Serotta certificate but I don’t think that the certificate makes the fitter. Does he/she do a lot of fitting, have the proper fit bike and cameras to test you on, have people that recommend him/her? Those would be the questions I’d ask. Steve

Thanks for your great feedback Steve!!

I’ll start applying your suggestions. I am running Conti GP 4000s 23c on my 23 mm wide stock wheelset (Giant PR-2 disc). Pressures are 100 psi rear and 90 psi front.

I don’t know much about the fitter’s experience, but he is the only “professional” fitter within 50+ miles and would like to give him a shot before venturing further. He does 2 to 4 bike fits a month (his primary function is as a physical therapist for high school athletes and he took on the bike fit as part of his personal passion for biking). Not a lot of feedback positive or negative about other people’s success with his fits. I am not aware of him doing any fits for professional level bikers. I do know he does the fit dynamically using a high speed stop action camera. He will do the fit on my bicycle mounted to a stationary trainer. The fit process requires two hours.

In the mean time (per your advice) I will keep my palm padded gloves on.

Thanks again!

Hi Steve, great article. Lots of in depth information…

I am interested in your opinion is about weight vs aerodynamics in smaller people (generally women, or me to be exact!), and how this affects bike choice….

I think that I’ve got my assumptions right:

1) Smaller people will have approx same power to weight ratio output, but less overall power output.

2) Smaller people will have reduced air resistance.

3) In smaller people the bike is a higher proportion of overall weight.

So I’m just trying to figure out what these assumptions combine to conclude in terms of aero bike vs SL road… I think they mean that the smaller a person is the more they should be at the SL road end? Or have I put 2 and 2 together and come up with 11?

Hope you can help. Thank you.

(Me, I’m 59kg & 170cm type of small, competitive triathlon type)

Rebecca, I mostly agree with your three points but I’m not sure about the conclusion it leads you to.

1) Lighter weight people will put out less power than heavier ones but can have a much greater power to weight ratio than heavier people if they train up to be stronger per pound. Generally speaking though, I’d think lighter people will have a greater power to weight ration as it’s easier to add power than it is to lose weight past a certain point

2) Shorter, narrower people will create less air resistance for the same aero position. But I think aero position is more important than body size in aerodynamics

3) Yes. (Thanks for an easy one!)

However, I think the only reason to buy an aero bike is if you are doing a lot of aero events (TT, Tri and the like) rather than based on your size or your aero or weight profile based on that size. Aero bikes are optimized for going fast and don’t handle as well as light weight road bikes that handle better and are generally good all around bikes against all performance criteria. You can certainly TT or Tri on a road bike, but they aren’t optimized for that. On the other hand, I wouldn’t want to do climbs or endurance riding and maybe not even club riding on an aero bike with out the TT bars (you don’t want to use them in group rides for safety reasons). The aero bike wouldn’t be as comfortable over time, wouldn’t be as precise in maneuvering and the aero benefit of an aero bike would be lost if you are drafting in a paceline. If you read the first part of this How To post, you can see that body position on any type of bike can significantly improve your performance more so than any kind of gear including bikes.

So, assuming you’ve got your aero position, training and all the other technique stuff dialed in, I think your bike choice has more to do with what you want the bike to do for you than your size.

Steve

I would caution against some of the data you use as “proof”. For example the graphic from Continental. Tire makers, want to start charging higher prices for the larger sized tires. And they need a campaign to convince the market to readjust for highter pricing. The best way to do this is a campaign to promote the false notion that larger tires are faster. The truth is, in their graphic, the thin tire is under-inflated, and the large one is over-inflated. At the correct pressure, their contact patches should have about the same shape. A larger lower-pressure larger tire is good for the flex it has to absorb pebbles in the road better, while other parts of the tire remain in contact with the road distributing some of your weight away(off of) from the pebble, thus slowing you down less. But I question whether there be any advantage at all on a smooth clean surface. I suspect all tires would perform about the same. If however, you have some fast turns on the course, larger tires aren’t a good idea.

And if you like criteriums, lighter wheels are far more important than it is suggested here. The energy required to rotate your wheel faster (acceleration) is felt much more in the difference in wheel weights.

And narrower tires are important for very fast cornering capability. There are just some cornering speeds at which a larger tire could put the riders in danger, it could just flop to the side, even with a wider rim.

Hi Timmi,

Tire width certainly generates some passionate views – me? – I rarely find ‘smooth clean surfaces’ where I ride, so I go with 28mm and am very happy.

I am interested in your comment ‘.. some cornering speeds at which a larger tire could put the riders in danger, it could just flop to one side, even with a wider rim’

~ Is this based on independent research or your personal judgment? If former, I would be interested in reviewing it if you can provide a link.

~ Perhaps my definition of ‘wider rim’ is different to you. I primarily use ENVE 4.5ARs [25/31mm inside/outside rims] on my custom Ti bike – I find that my confidence downhill has improved (say 5 mph faster). I have no idea how to allocate this improved handling between the frame geometry 9eg longer rear chain stay) and the wheels/tires.

~ while a little faster downhill, I certainly do not consider I corner anywhere close to ‘very fast’ – perhaps your concern only applies at extreme ‘racing’ speeds?

Happy cycling whatever tires you use.

I’ve just come across your webpage, tons of advice here for us normal road cyclists. I’ll have to spend more time reading your great tips. Cheers

Hi Steve,

Really appreciating your website and extremely impressed at how it has matured over the years. I’m thinking of getting Roval CLX 50 wheels, which are apparently 29.5mm wide! I am just wondering if I will have any problems with Ultregra 6800 brake callipers. I suspect but I wondered if you had any info on this.

Many Thanks Ian

Shouldn’t be a problem as long as you don’t go crazy with tire width.

“Over 40K/25miles, GCN calculated that would result in a 4-minute difference. I think it would probably be more like 2 minutes or less for most enthusiasts who can’t hold the speed that a 300 watt average output would generate over 25 miles and would lose the benefit of the higher reduction in drag at higher speeds. Nonetheless, even 2 minutes would be a huge savings.”

According to the linked GCN video, the result would be a full minute difference, not a four minute difference.

Hong, Good catch. I find those British accents a bit hard to understand sometimes. 🙂 I’ll fix the text accordingly. Thanks, Steve

Hi Steve,

I too got sucked into the idea that ditching gloves was smart to improve my aero profile until a crash at Masters Nats knocked some sense into me. I wish I could post a picture of my palm with half the skin missing to make the case for gloves. Or maybe video of me clenching down a small roll of paper towels with my teeth to handle the pain of cleaning the wound each day. Remember, when it comes to bike racing it’s not a matter of if, but when you’ll crash (btw, there was nothing I could have done to avoid this crash). I’m super aero conscious when it comes to cycling, but there is no way I’ll go without gloves again.